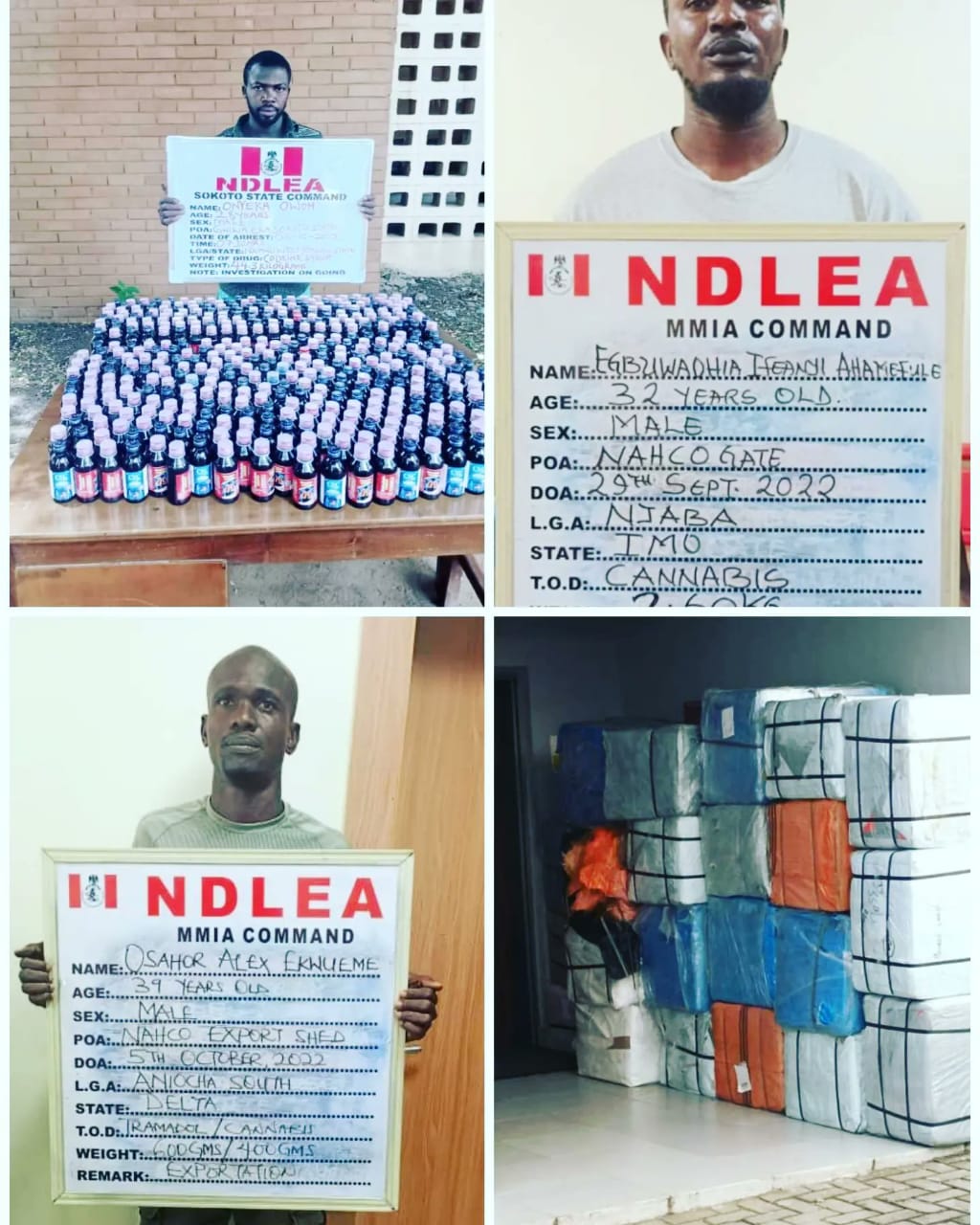

NDLEA intercepts 2.4 million tramadol pills at Lagos airport

By Ahmad Deedat Zakari The National Drug Law Enforcement Agency, NDLEA, disclosed that it has intercepted 2.4 million tramadol pills from Pakistan at the Murtala Muhammad International Airport in Lagos…