[OPINION]: Abba’s defection to APC: A betrayal rooted in shared corruption with Ganduje

In the ever-shifting landscape of Nigerian politics, few moves have sparked as much outrage and disillusionment as Abba’s recent defection from the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP) to the All Progressives Congress (APC). This decision, announced amid fanfare at the Sani Abacha Stadium in February 2026, is not merely a political realignment but a stark revelation of ideological convergence—one centered on the plunder of public resources. Abba’s embrace of the APC, under the guise of seeking federal support for Kano’s development, mirrors the very looting ethos that defined Abdullahi Ganduje’s tenure as governor. It is no coincidence; the two share a disturbing similarity in their approach to corruption and the mismanagement of Kano’s treasury, turning the state’s wealth into personal fiefdoms while ordinary citizens suffer.

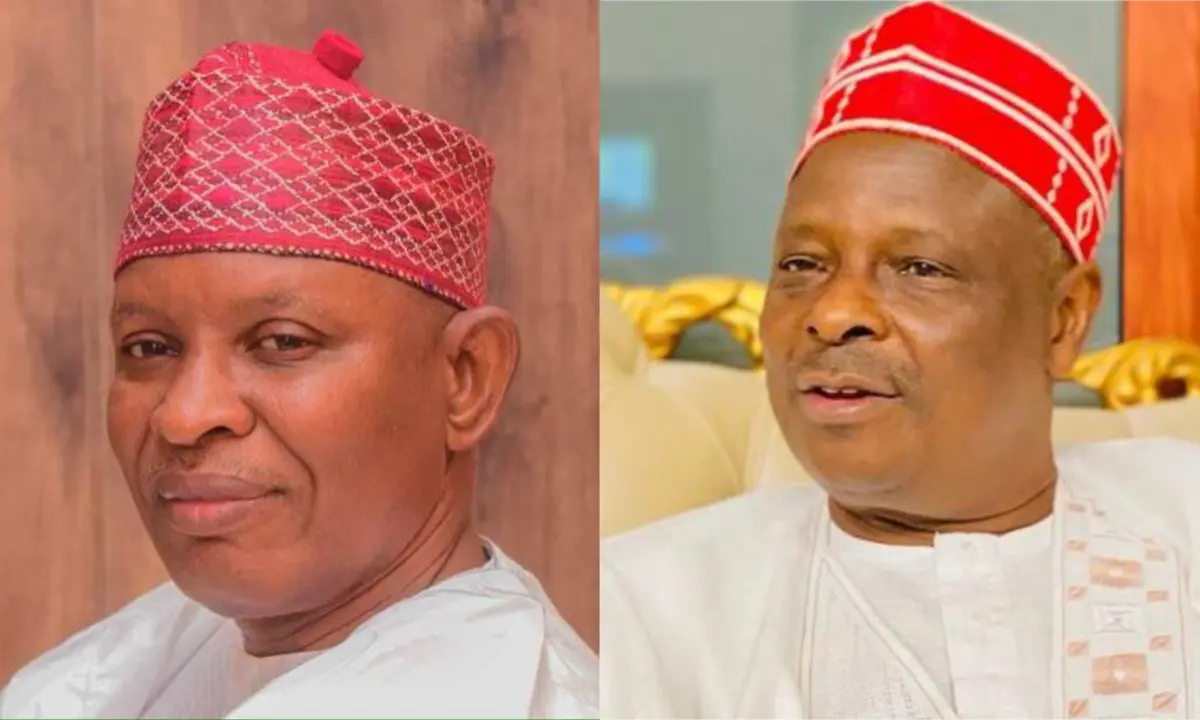

Ganduje’s legacy in Kano is synonymous with brazen corruption, epitomized by the infamous “Gandollar” scandal. In 2018, video footage surfaced showing Ganduje allegedly stuffing bundles of U.S. dollars—amounting to about $5 million—into his pockets, bribes extracted from contractors for state projects. This was no isolated incident; contractors revealed that Ganduje routinely demanded 15 to 25 percent kickbacks on every contract awarded during his administration from 2015 to 2023. The scandal led to investigations by the Kano Public Complaints and Anti-Corruption Commission (PCACC), which uncovered evidence of theft, abuse of office, and familial involvement in graft. Yet, even as charges piled up, including a $413,000 bribery case, Ganduje evaded full accountability, with court rulings limiting state probes and documents mysteriously vanishing during protests in 2024.

More damning is Ganduje’s role in the multi-billion naira Dala Inland Dry Port scandal. As governor, he awarded a N4 billion infrastructure contract for the port, which was meant to include a 20 percent equity stake for Kano State. Instead, he secretly transferred this stake to private entities, making his own children co-owners and denying the state its rightful share. This act of self-enrichment not only siphoned public funds but also exemplified a pattern of mismanaging state assets for personal gain. A key witness in the case was arrested at the airport in a suspicious twist, further fueling suspicions of cover-ups. Ganduje’s administration left Kano’s treasury depleted, with allegations of embezzlement running into billions, all while infrastructure crumbled and public services faltered.

It was precisely this rampant corruption and mismanagement of the public treasury that led to the overthrow of Ganduje and his allies in the 2023 elections. The people of Kano, long burdened by empty promises and drained coffers, had awakened to the realities of governance. They followed every misstep— from the kickback schemes to the vanishing funds—and channeled their frustration into the ballot boxes. The Kwankwasiya movement, with its red cap revolution, swept in on a wave of accountability, electing leaders who pledged to restore integrity. This seismic shift proved that when citizens are vigilant, no looting ideology can withstand the power of an informed electorate.

Now, turn to Abba, whose defection to the APC in January 2026—alongside 22 state assembly members and nine federal lawmakers—has exposed a parallel track record of corruption. Despite campaigning on a platform of zero tolerance for graft, Abba’s administration has been mired in scandals that echo Ganduje’s playbook. In August 2025, a N6.5 billion fraud scheme came to light, involving Abba’s Director-General of Protocol, Abdullahi Rogo, who allegedly diverted state funds through front companies, bureau de change operators, and personal accounts. The Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) launched probes, revealing how these funds were siphoned from the treasury under the noses of top officials.

The scandal widened when Abdulkadir Abdulsalam, then Accountant General and now Commissioner for Community and Rural Development, admitted to authorizing a N1.17 billion payment that formed the basis of the larger fraud. Investigators described it as a sophisticated money laundering operation, diverting resources meant for Kano’s development into private pockets. Civil society organizations, numbering about 20, demanded accountability, accusing Abba’s government of hypocrisy after it had vowed to prosecute Ganduje-era crimes. Even former Secretary to the State Government, Abdullahi Baffa Bichi, lambasted the administration for corruption “tenfold” that of Ganduje’s, citing evidence of mismanagement that could collapse the government before 2027.

These parallels are undeniable: Both leaders have been accused of using state contracts and equity deals to enrich allies and family, with billions vanishing through opaque channels. Ganduje’s dollar-stuffed pockets find a modern echo in Abba’s alleged BDC diversions, both representing a looting ideology that prioritizes personal gain over public welfare. Abba’s defection, justified as a bid for “federal backing and development,” is nothing more than a safe harbor in a party that has shielded Ganduje from full prosecution. It’s a union that undermines the anti-corruption promises Abba once made, aligning him with the very forces that bled Kano dry.

But history teaches us that the people of Kano will not stand idle. Just as they rose in 2023 to dismantle Ganduje’s corrupt empire, they are even more awakened today. Citizens are closely monitoring every government action, from budget allocations to contract awards, and they will not hesitate to enforce change through the ballot boxes come 2027. This defection is a desperate grasp at power, but it will only fuel the resolve of those who demand transparency.

Kano deserves better than this cycle of betrayal. The Kwankwasiya movement, with its unwavering commitment to transparency, education, and equitable development, stands as the true alternative. Founded on principles of integrity under Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, it has consistently exposed and fought such graft, from Ganduje’s era to now. As Abba cozies up to the APC, let this be a wake-up call for Kano’s people to rally behind a movement that puts the treasury in service of the masses, not the elite. The fight against looting ideologies must continue—stronger, unyielding, and rooted in the red cap revolution that truly represents hope for our state.

Dr Umar Musa Kallah is a writer and community advocate and can be reached via kallahsrm@gmail.com.