Khalifa Isyaku Rabi’u University, Kano, set to begin 2023/2024 session

By Muhammadu Sabiu

The Khalifa Isyaku Rabi’u University, Kano, is gearing up for an exciting chapter in its academic journey as it announces the commencement of activities for the 2023/2024 academic session.

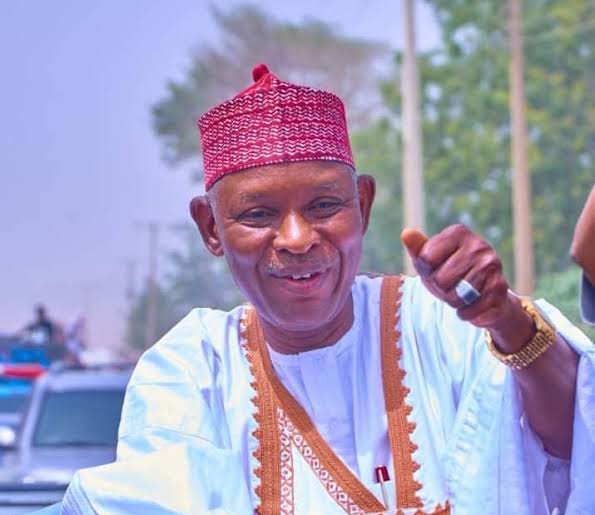

The announcement was made by Rabiu Ishaku Rabiu, the son of the university’s founder, shortly after the inauguration ceremony of the governing council.

Mr. Rabi’u conveyed that the university has meticulously prepared for a seamless inauguration in January 2023, ensuring that students can embark on their academic journeys without hindrance.

He raised concerns about the limited admission opportunities within Nigeria’s tertiary institutions, with only a fraction of admission seekers successfully securing spots each year.

Highlighting the urgency of the university’s establishment, Mr. Rabi’u referred to data from the World Bank indicating that a staggering 84.7% to 94.8% of candidates seeking admission in Nigeria were unable to secure places in existing institutions.

In 2018, the admission rate was reported as just 12.1%, underlining the pressing need for additional educational avenues.

“After obtaining the necessary licenses, inaugurating the board of trustees, and now the governing council, the management is in place, and the enrollment process is underway. We are fully funded and ready to hit the ground running,” Mr. Rabi’u affirmed.

“Our academic activities will commence by December/January, with all processes completed by the next month.”

The Vice-Chancellor of the university, Prof. Abdulrashid Garba, provided further insights into the institution’s readiness. He disclosed that discussions with the National Universities Commission (NUC) and the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) had been finalized.

While NUC initially approved 18 programs, two programs, LLB Shariah and Common Law, were temporarily put on hold due to specific requirements.

Prof. Garba commended the timely inauguration of the governing council, emphasizing its crucial role in supporting the management’s efforts to ensure a smooth takeoff.