By Uzair Adam Imam

Translators, language experts, and advertising practitioners in Northern Nigeria are irritated by shoddy Hausa on billboards, TV and radio stations, with some calling for an end to the practice.

The role of translation is to communicate ideas and messages across the audience. However, as those concerned individuals opined, shoddy translation is doing the opposite.

Beyond the expert communities, poor translation, especially from English to Hausa, is generating outrages in many quarters, especially as native speakers of the Hausa language demand better translation of their language.

A report by The Daily Reality disclosed how the Three Crowns Milk, Taira, and Stanbic IBT, among others, came under attack over poorly translated advertisements from English to Hausa placed on their billboards.

Experts have associated the flagrant flaws of advertising agencies and personnel with unprofessionalism. They said that the practice has grown into a disease which has since been ravaging the translation business in Nigeria.

Authority to blame

There are outrages by the relevant authorities that feel very disappointed by the terrible things in the name translation that continue to unfold these days.

A lecturer at the Department of Nigerian Languages, Bayero University, Kano, Dr. Muhammad Sulaiman, described the situation as unfortunate.

He said the way some people bastardise the translation business, especially English-Hausa translation, despite making a fortune in the business is pathetic.

Dr. Muhammad said, “Some of these people mostly do not bother about such violations but rather the money they are tapping out from the business.

“Even though translation is a profitable business, its knowledge should be considered above the profit. If you don’t have the knowledge, learn it or allow people with the skill to do the business.”

Also, a Kano-based translator, Bello Sagir Imam, decried the menace of quack and unprofessional translation ravaging the translation business today in Nigeria as unfortunate.

Imam, the CEO of English Domain, a translation company, blamed the relevant stakeholders for merely lamenting the menace without taking bold action to address it.

He added that the lack of English-Hausa translation companies in the country exacerbates the menace.

He argued that the loopholes gave space to the quack companies and will continue to bring more and worse translators until the proper measures are taken.

Imam stated, “Failure of the Northern Nigerian relevant stakeholders is an easy and thriving business environment for the quack but well packaged and connected companies mainly based in Lagos and few others in Abuja, but amazingly not in Kano.

“For instance, in the North, with the entire daily complaining razzmatazz, there is no single English-Hausa-English translation company or one where such service is among their services.

“These loopholes birthed the quack companies and will continue to birth more and worse translators until the right measures are executed.”

We need support

Imam further lamented how the lack of support from relevant stakeholders discourages aspiring English-Hausa translators.

He said, “Most stakeholders do not help the aspiring English-Hausa translators despite being Hausa native speakers and linguists, Hausa or English graduates, simply because they don’t have a prior relationship with the helpers.

“For instance, if you are not their student, those in academia will not help you. The journalists will not help you if they don’t know you.

“I feel challenged as a relevant stakeholder to walk the talk, to mitigate the problems and inspire others to wake up from their deep sleep.”

What is the root cause of quack translation?

A communication scholar from the Mass Communication Department, Professor Mainasara Yakubu Kurfi, traced the root of quack translation, shedding light on the impact of a shoddy translation on advertising.

Professor Kurfi said, “If you look at what is happening in advertising industries, you can simply conclude that there is no professionalism – lack of professionalism in the sense that most of the advertising agencies and agents did not undergo practical formal education that will avail them the opportunity to understand what advertising is and what advertising is not, as well as understanding the techniques of advertising in appealing to the public without going into their religion, culture and even norms and practices.

“That is why you see several problems, particularly with billboards and adverts. I remember I did my master’s dissertation on billboards.

“Most of these translators, either from English to Hausa or Hausa to English, are not native speakers. They are generally from Lagos, probably Yoruba by tribe, and they do not really understand the nature of the language of reception – from English to Hausa or from Hausa to English.

“Some of the techniques that you consider in terms of translation they understand, they don’t have knowledge of that.

“Also, you find out that most of these translators are based in Lagos. They are not from Northern Nigeria. Therefore, they don’t understand the language itself.

“And we do not have many advertising agencies here in Kano that will now take cognisance of those traditions and norms. Therefore, it is not surprising to see this kind of problem.

Native speakers must key in the advertisement

Professor Kurfi said that to tame the menace of native speakers, in this sense, typical Hausa/Fulani must key into the advertisement business.

He said, “The only way forward is to allow our people to enter the advertising industry. I don’t know why our people, particularly typical Hausa Fulani, are running away from advertising. Let our people be into advertising.

“Let them understand the techniques and practice of advertising, the procedures, the rules and regulations governing advertising, in the print media, in the broadcast media, even on the online media platforms, as well as billboards and adverts.

“When they understand that, you discover these problems will undoubtedly be minimal. They will be contracted to translate from English to Hausa or From Hausa to English.

“Another way out is to let our people, particularly the graduates of mass communication, establish independent advertising agencies responsible for all this kind of advert placement in the media organisations.

“But when our people are running away, the advertising agencies or the producers or manufacturers have no option but to contract the service of the people from the southern part of Nigeria – and this is why you see all these kinds of problems happening.”

It’s posing a serious challenge to us – APCON

The President of the Advertising Practitioners of Northern Nigeria, Sammani Ishaq, lamented the rising number of cases of poor translation.

He said that Advertising Practitioners have been working to end the problem over the years.

Sammani Ishaq said shoddy Hausa translations usually affect the persuasive aspect known for advertising and that consumers patronise the product out of desperation, not because they are being persuaded.

He said, “This is a serious issue we have been trying to address over the years. In doing so, we held many meetings and organised different programs. We even formed a forum we named Advertising Practitioners of Northern Nigeria.

“The issue is beyond imagination because most advertisers are from the southern part of the country and are either Igbo or Yoruba. It was not for ten years that northerners started advertising businesses. And, up till now, the advertising agencies are not numbered to ten.

“And what they mostly do is to hire their friends from southern Kaduna, who do not fully understand the language, let alone translate it correctly, or people who have served or had been in the north for a while.

“For this reason, the translators are not even Hausa and don’t fully understand the language. So, they usually hire people from southern Kaduna or those who have served in the north for translation.

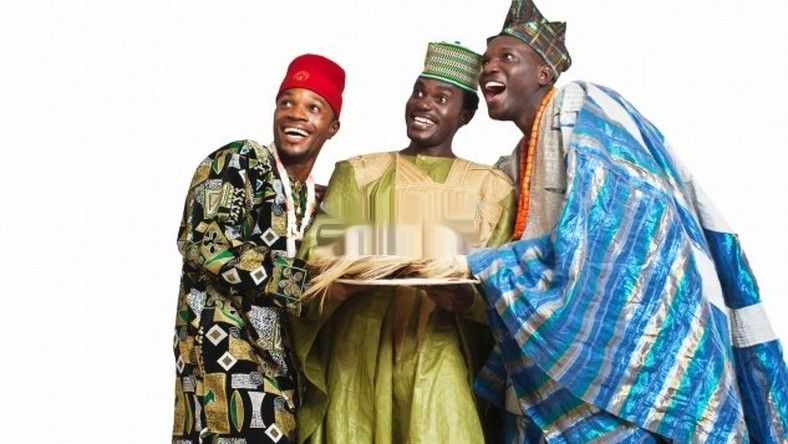

“And, sometimes, even in the north, people mostly hire Kannywood or Nollywood actors and actresses for advertising. These people are unprofessional and lack the basis of advertisement. Hence, people purchase products not because they are persuaded to but only because the product has become necessary for them to buy.

We will deal with unregistered advertising agencies

Sammani also threatened that any unregistered advertising agency caught would be dragged before the court to face the music.

He stated, “And for this reason, APCON provided a law signed by the former president of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari, before he left office on May 16, 2023. The law stated that any unregistered advertising practitioner caught practising advertising must be dealt with.”