By Prof. Abdalla Uba Adamu

Recently, an extremely prestigious academic journal requested that I review a film made by a Nigerian. I was surprised, as that is Muhsin Ibrahim’s forte. Further, I really don’t watch Nigerian films, aka Nollywood, personally preferring African Francophone directors. Nevertheless, I agreed to do the review.

However, the link they sent for the film was password-protected. I informed them, and they requested the filmmaker to send the password. Being a request from a highly prestigious journal, he sent the code, and I was able to get on the site and watch the film online. I was surprised at what I saw and decided to delve further into these issues. Before doing that, I wrote my review and sent it off. The film, however, set me thinking.

Like a creeping malaise, Nollywood directors are rearing their cameras into the northern Nigerian cultural spaces. Again. The film I reviewed for the journal was “A Delivery Boy” (dir. Adekunle Adejuyigbe, 2018). It was in the Hausa language. None of the actors, however, was Hausa, although the lead actor seems to be a northerner (at least from his name since an online search failed to reveal any personal details about him).

Nothing wrong with that. Some of the best films about a particular culture were made by those outside the culture. Being ‘outliers’, it often gave them an opportunity to provide a more or less balanced and objective ‘outsider’s perspective’ of the culture. Alfonso Cuarón, a Mexican, successfully directed “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” (2004), while Taiwanese director Ang Lee did the same with “ Brokeback Mountain” (2005), even earning him an Oscar.

In 2006 Clint Eastwood, an American, directed “Letters From Iwo Jima.” The cast was almost entirely Japanese, and almost all of the dialogue was in Japanese. It was very well-received in Japan, and in fact, some critics in Japan wondered why a non-Japanese director was able to make one of the best war movies about World War II from the Japanese perspective. Abbas Kiarostami, an Iranian filmmaker, directed his film, “Certified Copy” (2020) in Italy, which contained French, Italian, and English dialogue starring French and British actors.

British director Richard Attenborough successfully directed Ben Kingsley in the Indian biopic Gandhi (1982). The film was praised for providing a historically accurate portrayal of the life of Gandhi, the Indian independence movement and the deleterious results of British colonization of India. It took away eight Oscars. American director Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List” (1993) on a German, Oskar Schindler, was equally a powerful portrayal of an auteur genius by a “non-native”. The film won seven Oscars.

In each of these examples, the directors approached their subject matter with a clean, fresh and open mind that acknowledges the cultural sensitivities of the subject matter. My point is that a person, outside of a particular cultural context, can make sensitive films that portray the culture to his own culture as well as other cultures. That is not, however, how Nollywood plays when it focuses its cameras on northern Nigerian social culture. Specifically Muslims.

I just can’t understand why they are so fixated on Muslims and the North. If the purpose of the ‘crossover’ films (as they are labelled) they make is to create an understanding of the North for their predominantly Southern audiences, they need not bother. Social media alone is awash with all the information one needs about Nigeria—the good, the bad and the ugly. You don’t need a big-budget film for that. Or actors trying and failing to convey ‘Aboki’ accents in stilted dialogues that lack grammatical context.

Yet, they insist on producing films about Muslim northern Nigeria from a jaundiced, bigoted perspective, often couched with pseudo-intellectual veneer. To sweeten the bad taste of such distasteful films, they pick up one or two northern actors (who genuinely speak the Hausa language, even if not mainstream ethnic Hausa) and add them to the mix, believing that this will buy them salvation. For southern Nigerians, anyone above the River Niger is ‘Hausa’.

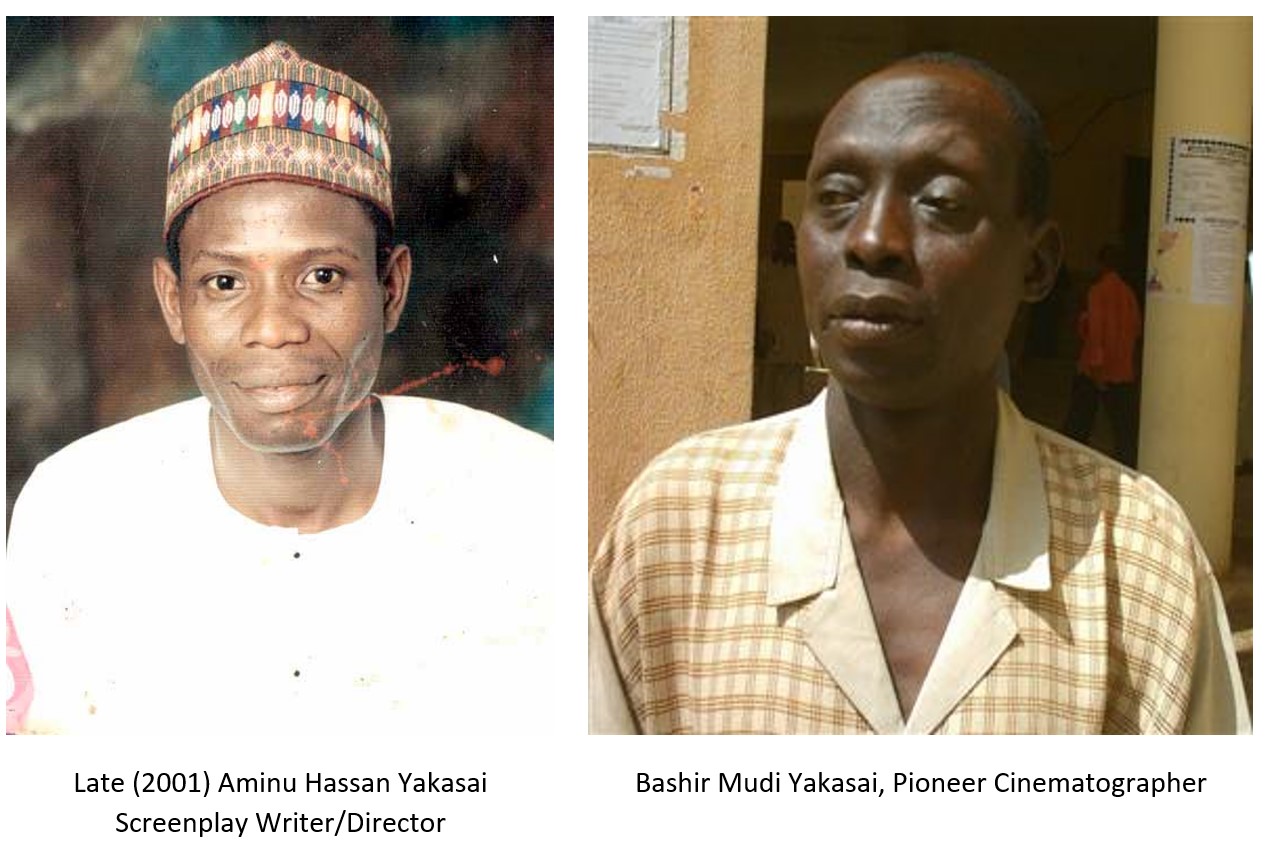

They started in the early 2000s, and people just ignored them. The directors then included Oskar Baker (Ɗan Adamu Butulu, Abdulmalik), Yemi Laniyan (Makiyi, Uwar Gida), Tunji Agesin (Halin Kishiya), Matt Dadzie (Zuwaira), I. Nwankwo (Macijiya) and many others. These came on the heels of the massive success of “Sangaya” (dir. Aminu Muhammad Sabo, 1999) when this particular film opened up the northern Nigerian film market.

Those Nollywood producers jumped into cash on the popularity of Hausa films and made their own for northern markets. For the most part, these early ‘crossover’ films that I refer to as ‘Northern Nollywood’ were fairly mild and evoked no reaction. They were still rejected, as the Hausa can be the most discriminatory people you can come across. If you are outside their cultural universe, you remain there. Forever.

The few Kannywood actors eager to be seen on the ‘national stage’ allowed themselves to be used to deconstruct Islam and Muslims on the altar of filmmaking in subsequent Northern Nollywood films. Let’s not even talk about character misrepresentation, which Muhsin Ibrahim has written extensively about. In these scenarios, the usual tropes for northerners in Nollywood films is that of ‘Aboki’ (a term southern Nigerians believe is an insult to northerners, without knowing what it means), ‘maigad’ (security), generally a beggar. If they value an actor, they assign them an instantly forgettable role rather than a lead. Granted, this might be more astute and realistic marketing than ethnicity because it would be risky to give an unknown Hausa actor a significant role in a film aimed at southern Nigerians.

A few of these types of portrayals in Nollywood included Hausa-speaking actors in films such as The Senator, The Stubborn Grasshopper, The World is Mine, Osama Bin La, Across the Border and The Police Officer.

When Shari’a was relaunched from 1999 in many northern Nigerian States, it became an instant filmic focus for Nollywood. A film, “Holy Law: Shari’a” (dir. Ejike Asiegbu, 2001) drew such a barrage of criticism among Hausa Muslims due to its portrayal of Shari’a laws then being implemented in northern Nigeria that it caused credibility problems for the few Hausa actors that appeared in it. With neither understanding of Islam nor its context, the director ploughed on in his own distorted interpretation of the Shari’a as only a punitive justice system of chopping hands, floggings, and killings through foul-mouthed dialogue. As Nasiru Wada Khalil noted in his brilliant essay on the film (“Perception and Reaction: The Representation of the Shari’a in Nollywood and Kanywood Films”, SSRN, 2016) “the whole story of Holy Law is in itself flogged, amputated and killed right from the storyline.”

“Osama bin La” (dir. MacCollins Chidebe, 2001) was supposed to be a comedy. No one found it funny in Kano. Despite not featuring any northern actor, it was banned in Kano due to its portrayal of Osama bn Ladan, then considered a folk hero. The film was banned to avoid a reaction against Igbo merchants marketing the film. I was actually present in the congregation at a Friday sermon at Kundila Friday mosque in Kano when a ‘fatwa’ was issued on the film. Even a similar comedy, “Ibro Usama” (dir. Auwalu Dare, 2002), a chamama genre Hausa film, was banned in Kano, showing sensitivity to the subject matter.

The reactions against crossover films seemed to have discouraged Nollywood producers from forging ahead. They returned in the 2010s. By then, northern Nigeria had entered a new phase of social disruption, and Nollywood took every opportunity to film its understanding of the issues—sometimes couched in simpering distorted narrative masquerading as social commentary—on society and culture it has absolutely no understanding of.

In “Dry” (dir. Stephanie Linus, 2014), the director developed a sudden concern about ‘child marriage’ and its consequences. Naturally, the culprits of such marriage, as depicted in the film, are sixty-year-old men who marry girls young enough to be their granddaughters. The director’s qualification to talk about the issue (which was already being framed by child marriage controversy in the north) was that she has ‘visited the north’ a couple of times. With the film, if she could get at least “one girl free and open the minds of the people, and also instruct different bodies and individuals to take action, then the movie would have served its purpose.” The ‘north’ was living in darkness, and it required Stephanie Linus to shed light on ‘civilization’.

“A Delivery Boy” (dir. Adekunle Adejuyigbe, 2018) that I reviewed was about an ‘almajiri’ in an Islamic school who was kidnapped from the school, to begin with and repeatedly raped by his ‘Alamaramma’ (teacher). The almajiri somehow acquired sticks of dynamite to create a suicide vest and vowed to blow himself up—together with the teacher. The Alaramma in the film lives in an opulent mansion, far away from the ‘almajirai’. In this narrative universe, the ‘almajiri’ do not learn anything and are unwilling rape victims of their teaches who actually kidnapped them and forced them into the schools.

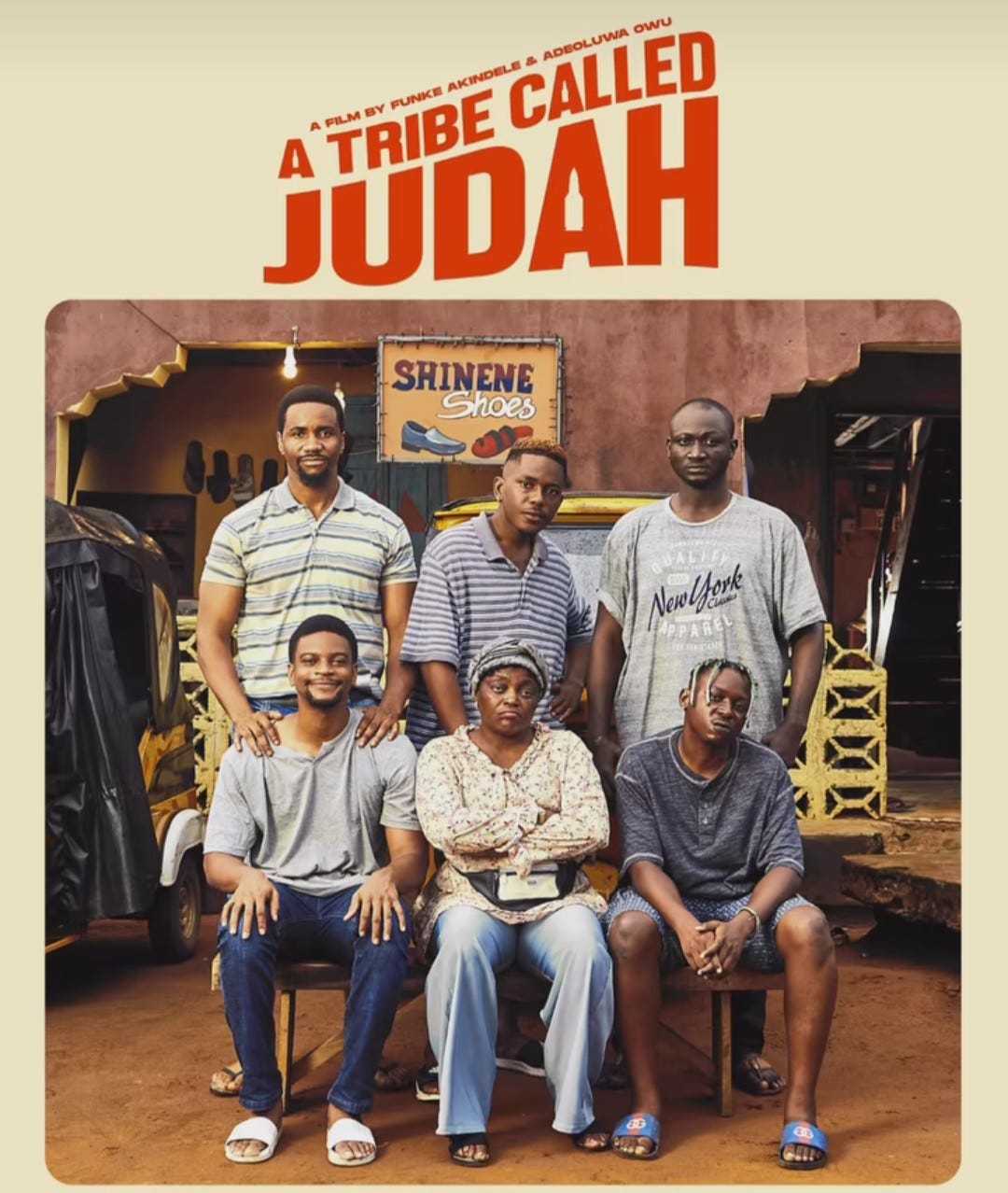

“The Milkmaid” (dir. Desmond Ovbiagele, 2020) evokes the idealistic picture of a Fulani milkmaid and became a basis for a Nollywood film. Instead of focusing on the political economy of the Fulani milk trade, the film focused on the trope of terrorism. “The Black Book” (dir. Editi Effiong, 2023), touted as ‘Nigeria’s John Wick’ shoots a significant portion in ‘the north’ – with ‘Islamist’ hijab-wearing females touting assault rifles hidden underneath their hijab. “Jalil” (dir. Leslie Dapwatda, 2020) visits the recurrent theme of kidnapping for ransom. In the north, of course.

Then came the latest, “Almajiri” (dir. Toka McBaror, 2022). Claimed to be a true-life story (although it is not clear whether it happened to specific people or based on what the director believed to be a common event), it featured muscle-bound badass types of thugs with guns and dreadlocks as Almajirai. The film reinforces the southern Nigerian trope of any beggar in the north being an Almajiri. Such ‘almajiris’ are kidnapped and sold into virtual slavery and horribly abused. The idea is to blame the parental irresponsibility of northerners.

For southern Nigerians, especially the Nollywood crowd, an ‘Almajiri’ is a beggar, a product of a failed education system, a terrorist, a bandit, and an ‘aboki’. They use concocted figures bandied about by alphabet soup agencies to proclaim ‘over 10 million almajiri are out of school’ and, therefore, twigs of the terrorism inferno. How can someone who has been part of a system of education for over half a century be considered out of school? But for Nollywood, if it is not ABCD, then it is not education.

“Northern Nollywood” films are the precise reasons why there will ALWAYS be different film cultures in Nigeria. Kannywood talks to its publics, happily churning out now TV shows that address issues it deems relevant—in its own way. Both the northern and southern parts of the country (covering the three major languages) were actively engaged. However, they were mutually non-legible to each other. This was essential because they operate on virtually opposing cultural mindsets – making the emergence of a truly “Nigerian cultural film” impossible.

Quite a few writers seem to suggest that Kannywood is a ‘subset of Nollywood’, and indeed, many would prefer for the term Kannywood (created in 1999 by a Hausa writer) to be dispensed with and replaced with Nollywood (created in 2002 by a Japanese Canadian writer). It is to protect our cultural representation in films that I stand as a lone voice in advocating for a ‘Hausa Cinema’ to reflect the cultural universe of the Hausa.

Professor Abdalla Uba Adamu can be reached via auadamu@yahoo.com.