By Bashir Uba Ibrahim, PhD.

Book Title: An Introductory Hausa Linguistics

Author: Isa Mukhtar

Pages: 167

Publishers: Bayero University Press

Year: 2024

Two weeks ago, I visited Prof. Isa Mukhtar after we concluded one of the parallel sessions organised for a national conference on the works of Aliyu Kamal, in which I served as a rapporteur. The event was held at the Department of Linguistics and Foreign Languages, which was renamed the Department of Linguistics and Translation following the unbundling and upgrade of the former Faculty of Arts and Islamic Studies to the College of Arts and Islamic Studies.

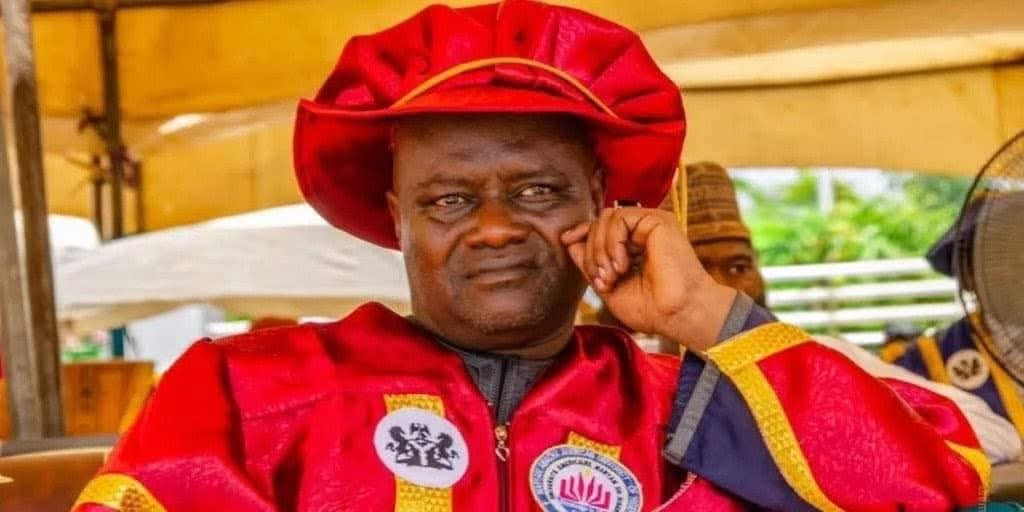

Prof. Isa Mukhtar is one of the most academically generous teachers I know. After exchanging greetings, he gifted me his newly published book titled An Introductory Hausa Linguistics, which I intend to review here briefly. Unlike previous books on Hausa grammar and linguistics, Mukhtar, in this thirteen-chapter book, attempts to simplify the branches of linguistics by extensively drawing on examples from the Hausa language and redefining some linguistic terms. This review is by no means exhaustive or comprehensive, as it would be difficult to do full justice to the book in this limited space.

Chapter one, which is entitled ‘Views on the Origin of Language’ (Ra’ayoyi a kan Asalin Harshe), dissects some of the speculations regarding the origin of language. He addresses the speculations regarding the origin of language by citing Zarruk’s views on the phenomenon, including divine creation, man’s discovery, man’s invention, and man’s evolution from a human perspective. He thus attempts a glottochronological examination of Hausa and Amharic, the language of Ethiopia, and Hausa and Coptic, the language of Egypt, in his effort to relate the origin of Hausa with its cognate languages in Africa.

Chapter two, titled ‘Introduction to Language’ (Gabatarwa a kan Harshe), discusses various functions of language. Citing relevant examples from doyen linguists like Fowler (1974) and Leech (1974), he nominally examines the general functions of language, buttressing the thesis with examples from Hausa. The chapter also briefly explains numerous linguistic forms (nau’oi a cikin harshe) in which he shows arbitrary and non-arbitrary forms of language.

The third chapter is titled ‘Historical Linguistics and Stylistics’ (Tarihin Nazarin Harshe da Ilimin Salo). Here, the author provides a historical analysis of the origin and development of linguistics as a field of study from antiquity to the present day. Various schools and movements that shaped major linguistics trends and ideas, such as structuralism (bi-tsari) and its subsidiaries like the Copenhagen school (makarantar Copenhagen), American structural linguistics (Bi-tsari a marajtar harshe ta America), French structuralism (Bi-tsarin Faransa), Prague school (makaranyar Prague), rationalism (na tunani), and empiricism (gogayya). The chapter also attempts to link structuralism with stylistics by discussing some of the stylistics scholars influenced by structuralism, such as Charles Bally, Roman Jakobson, and Michael Riffaterre. These scholars developed their theory on the style of communication and contributed to generative stylistics.

Chapter four, ‘Functional Linguistics and Stylistics’ (Harshen Aiwatarwa da Ilimin Salo), builds on the previous chapter by examining stylistics (ilimin salo) from a systemic functional linguistics perspective. In this chapter, the writer attempts to appropriate Halliday’s theory of stylistics and apply it to Hausa data by extensively drawing examples from it. Thus, Halliday’s main conception of the stylistics function of language into ideational, interpersonal and textual was heavily domesticated and linked with Hausa.

The fifth chapter titled ‘Classification of African Languages’ (Rarrabewa Tsakanin Harsunan Afirka). In this chapter, the author bases his classification of African languages on Greenberg (1966), in which he classified African languages into four phyla, namely, Afro-Asiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo and Nilo-Saharan. He attempts to trace the Hausa language to the West-Chadic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. He establishes its relationship with cognate languages in Nigeria, such as Bole, Kare-Kare, Warji, Ron, and Bade.

Chapter six, which is entitled ‘Syntax and Grammar’ (Ginin Jumla da Nahawu), makes a historical examination of grammar from a Greek grammarian, Dionysius Thrax, traditional grammar (Nahawun gargajiya), structural grammar (nahawun bi-tsari), finite state grammar (nahawun kwakkwafi), phrase structure grammar (tsarin nahawun yankin jumla), generative grammar (nahawun tsirau), transformational grammar (nahawun rikida/taciya), transformational generative grammar (nahawun taciya mai tsira), etc.

The seventh chapter, ‘Advanced Syntax’ (Babban Nazarin Ilimin Harshe) served as a build on its preceding chapter. The chapter makes a deeper examination of the extended standard theory by Chomsky, looking at Government and Binding Theory of Syntax and its application in the Hausa language. While chapter eight, which is titled ‘Issues in Hausa Syntax’ (Muhimman al’amura a tsarin jumla), builds on the previous one by examining extended standard theory and its syntactic operators and how they can be applied in Hausa.

Chapter nine, which is entitled ‘Phonetics and Phonology’ (furuci da sauti), makes an extensive examination into Hausa phonetics and phonology. It looks at articulatory, acoustic, and auditory phonetics, drawing heavily from Sani (2010). It also discusses Hausa phonological inventories and processes as the backbone of generative phonology, such as assimilation, dissimilation, palatalisation, labialisation, nasalisation, metathesis, polarisation, etc. Meanwhile, chapter ten titled ‘Morphology’ (Ilimin Tasarifi) discusses Hausa morphological structure, morphemes, types of morphemes, criteria for identification of morphemes, morphological processes and word formation processes by citing Abubakar (2001) to exemplify his discussion.

Chapter eleven, ‘Dialectology’ (Ilimin Karin Harshe), explores the relationship between language and society by examining major sociolinguistic aspects and relating them to Hausa languages, including argot, slang, jargon, sociolects, Hausa dialect variety, and language and culture. Chapter twelve, which is entitled ‘Semantics’ (Ilimin Ma’ana), makes a historical examination of the term ‘semantics’ and shows how it is problematic in relation to linguistic analysis. The chapter also examines the relationship between semantics and linguistics, as well as Hausa semantic change, collocations, componential analysis, speech-act, descriptive semantics, theoretical semantics, and general semantic theories. The chapter also delves into the relationship between semantics and other branches of linguistics, such as morphology, phonology, and syntax, in what can be called a ‘linguistic interface’.

Meanwhile, the thirteenth chapter, which is the final chapter, is titled ‘Sociolinguistics’. It examines the issue of multilingualism in Nigeria, with Hausa as one of the major languages. It examines how sociolects served as social varieties of language that are determined by social factors rather than geography, citing examples with Hausar masu kudi, Hausar sarakai, Hausar malamai, Hausar ‘yan daba, Hausar likitoci, etc.

Overall, this book, intended as an introductory text, aims to acquaint readers with foundational topics in Hausa linguistics. Its straightforward presentation and accessible language make it especially useful for beginners. However, the author’s effort to simplify the content may have been overextended, leading to notable gaps. Crucially, important subfields such as psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics, applied linguistics, forensic linguistics, and computational linguistics are not mentioned at all.

Another significant omission is the absence of Ferguson (1970), particularly given the discussion on dialectology—a field in which Ferguson was a major contributor—as well as the exclusion of key works on Hausa dialectology such as Musa (1992). Similarly, in Chapter Twelve, the focus is limited to structural semantics, with no mention of Hausa cognitive semantics or relevant contributions like Bature (1991) and Almajir (2014).

The book appears to lean heavily towards stylistics and syntax, dedicating two chapters to the former and three to the latter, specifically Chapters Six through Eight. While these topics are undoubtedly important, the focus becomes somewhat disproportionate. For instance, in the discussion of Government and Binding Theory and complementation, the author omits important works such as Yalwa (1994), Issues in Hausa Complementation and Mukhtar (1991), Aspects of Morphosyntax of Hausa Functional Categories, both of which could have enriched the analysis from a Hausa linguistic perspective.

In conclusion, as Ibrahim (2008: 260) aptly states, “There is no perfect text. But as human life itself, the various imperfections of our life provide a constant challenge to us as scholars embroiled in the learning process.” Despite the criticisms above, Mukhtar’s ability to present complex topics clearly and subtly remains commendable. This book stands out as one of the more accessible introductory texts on Hausa linguistics, suitable for both students and newcomers to the field.