The Almajiri System: A broken legacy we must bury

By Umar Sani Adamu

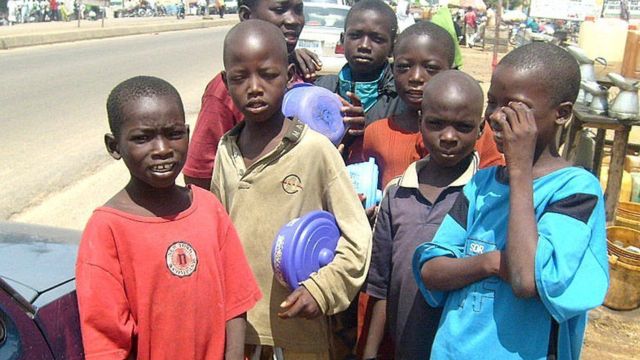

The Almajiri system, once a noble pursuit of Islamic knowledge, has degenerated into a humanitarian disaster spread across Northern Nigeria. From the streets of Kano to the slums of Sokoto, thousands of children wander barefoot, hungry, and hopeless victims of a tradition that has outlived its purpose.

The idea behind Almajiranci was simple: young boys, mostly from rural or poor families, would be sent to Islamic scholars for religious education. But over time, what began as a pathway to learning became a pipeline to poverty, abuse, and neglect. Today, these children beg for survival, live in unhygienic conditions, and face constant exposure to criminality and exploitation.

Every year, thousands more are pushed into this cycle. With no formal curriculum, no sanitation, no feeding structure, and no monitoring, the system violates every principle of child welfare and human dignity. Many of these almajiris live in overcrowded, unventilated rooms, sometimes as many as 18 children in a single space, with no access to health care, no protection, and no future.

While governments talk reform, very little action meets the urgency. Integration programs are underfunded, religious institutions are left unchecked, and families often forced by poverty continue to submit their children to this outdated system. Meanwhile, the streets of Northern Nigeria grow more unsafe as vulnerable children are manipulated by extremist groups and criminal syndicates.

Let’s be clear: the Almajiri system, in its current form, is not education. It is abandonment. It is state-sanctioned child endangerment masquerading as religion. Any society that claims moral or spiritual uprightness cannot continue to tolerate this level of systemic neglect.

What Northern Nigeria needs is not a patchwork of reforms, but a complete overhaul. Islamic education should be formalised, monitored, and integrated into the broader national curriculum. Children should learn in safe environments where Qur’anic knowledge is integrated with literacy, numeracy, hygiene, and vocational training. Religious scholars must be trained, certified, and held accountable.

Above all, we must shift the responsibility from children back to adults. Governments, communities, parents, and religious leaders must admit the system has failed and work together to end it. The Almajiri child deserves more than survival. He deserves dignity, opportunity, and a future.

This is not just a social concern. It is a national emergency.

Umar Sani Adamu can be reached via umarhashidu1994@gmail.com