By Prof. Abdalla Uba Adamu

It happened 40 years ago. A friend’s wife in Kano had delivered a bouncing baby boy. My friend chose Maikuɗi as the name for the baby. The families on both sides were having none of this. Maikuɗi was not a name, they argued. But he saw nothing wrong with it – a nice traditional Hausa name. He was adamant. They were adamant. Cue in A Mexican Standoff.

Three days before the naming ceremony, he blinked first and apparently gave up. With a glint in his eyes, he decided to name the child Ibrahim. A beautiful Hebrew name but cognately shared by both Muslims and Christians (from Abraham, the father of all). Everyone was happy – until it dawned on everyone that Ibrahim was the name of my friend’s father-in-law. Tricky. In Hausa societies, the names of parents are never uttered. In the end, everyone ended up calling the boy Maikuɗi! Right now, the boy is a successful international businessman living in the Middle East. Earning serious cash and living up to his name – which means one born on a lucky day. Or Tuesday.

A few years later, the same friend’s wife gave birth to a beautiful baby girl. He decided to name her Tabawa. Objections reloaded. Cue in Dog Day Afternoon. As previously, my friend blinked first. He decided to name her Hajara, another cognate of Hagar, the wife of Abraham. It also happened to be the name of his eldest sister. His mother could not utter it – both the Hausa and Fulani system of cultural relations prohibit mothers from calling the names of their first series of children. In the end, everyone ended up calling the child Tabawa. She is currently a university lecturer and a doctoral student in Nigeria. Living up to her name – which means Mother luck, or the name given to one born on Wednesday (in Kano; in Katsina, it is Tuesday) is considered a lucky day. Two children, both lucky in their lives. Their traditional Hausa names became their mascots as they glided successfully through life.

So, why the aversion to Hausa ‘traditional’ names? You can’t name your child Maikuɗi, but everyone will applaud Yasar (wealthy – mai kuɗi?). Or Kamal (perfection). Or Fahad (panther). Or Anwar (bright). Or Fawaz (winner). You can’t name your daughter Tabawa, but it is more acceptable to call her Mahjuba (covered). Or Samira (night conversationist –TikToker?). Name your daughter ‘Dare’, and you are in trouble. Change it to Leila, and you out of it, even though this is an Arabic for ‘dare’ (night).

A lot of the names the Muslim Hausa currently use have nothing to do with Islam. Bearers of such names rarely know their actual meaning or context. They were Arabic and forced on us by the Cancel Culture that attaches a derogatory ‘Haɓe’ coefficient to anything traditional to the Hausa.

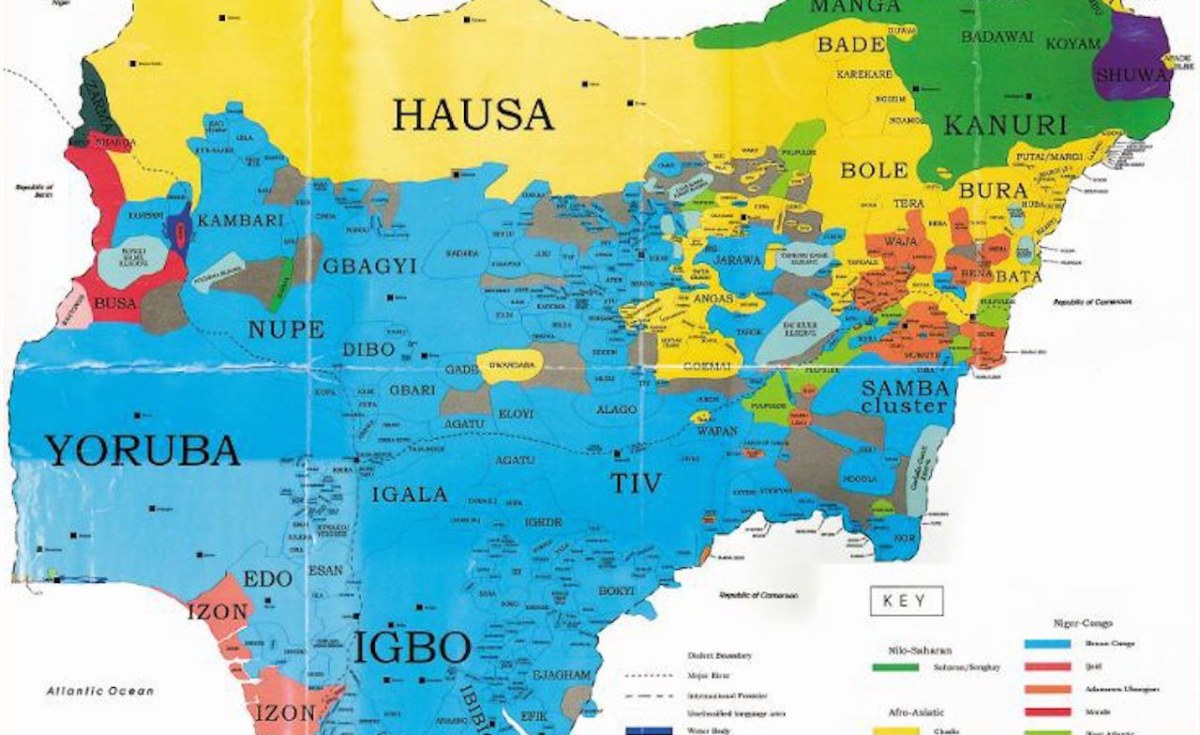

Therefore, my friend, whose family story I just related, another friend and I decided to get together and be Wokish about traditional Hausa names. Paradoxically, none of us is genetically Hausa (whatever that might mean) – one had roots in north Africa, another had Kanuri heritage, and one had Agadesian and Torodbe roots – but all of us self-identified, with absolute honour and tenacity, as Hausa. None of this ‘Hausa-Fulani’ aberrational nonsense.

‘Hausa-Fulani’ appellation, in my view, is a Nigerian Cancel Culture device to suppress the Fulani culture. The Fulani may have conquered the ruling of the Hausa (except in one or two places) and imposed their rule. The Hausa, on the other hand, have linguistically conquered the Fulani. In Kano, claiming Fulani heritage is considered anthropological purity – without knowing a single word of Fulfulde (the Fulani language). Substituting rulers does not get rid of the general populace who remain what they are.

The third friend then took the task with gusto. He spent over ten years compiling authentic traditional Hausa names that have absolutely nothing to do with ‘Maguzanci’ (the label gleefully and contemptuously attached to any Hausa who is not a Muslim by the Hausa themselves) before Islam in about 1349, at least in Kano). He also collected names that had only a tinge connection to Islam. The end product was a hitherto unpublished list of 1001 authentic, genuine, traditional Hausa names that reflect the cosmology of the Hausa.

Hausa’s anthropological cosmology reflects the worldview and belief system of the Hausa community based upon their understanding of order in the universe. It is reflected in their naming system – just like any other culture. The Yoruba Muslims, for the most part, have retained this attachment to their traditional cosmology. Farooq Kperogi has done wonderful work on Yoruba naming, although with a focus on their adaptation of Muslim names. The failure of the Hausa to do so was, of course, due to the suffocating blanket of Cancel Culture that the Hausa had been suffering for almost 229 years.

Now, let’s look at the names and their categories. The first category I created from the 1001 Names, which I edited, revolved around Being, Sickness and Death. As noted earlier, the traditional Hausa centre their naming conventions on ecological and cosmological observations—using time, space and seasons to mark their births. Based on this, the first naming convention uses circumstances of birth. This category of names refers to the arrival of a child after another child’s death, the death of a parent, the sickness of the child immediately after being born or a simple structure of the child that seems out of the ordinary. Examples include:

Abarshi. This is derived from the expression, ‘Allah Ya bar shi’[May Allah make him survive]. A male child was born after a series of miscarriages. A female child is named Abarta. A protectionist naming strategy is where the child is not given full loving attention after birth until even evil spirits note this and ignore it and thus let him be. Variants include Mantau, Ajefas, Barmani, Ajuji, and Barau. Now you know the meaning of Hajiya Sa’adatu ‘Barmani’ Choge’s name – the late famous Hausa griotte from Katsina (1948-2013).

Then there is Shekarau, derived from ‘shekara’, a year. A male child is born after an unusually long period of gestation in the mother’s womb. A variant of this name is Ɓoyi [hide/hidden]. A female child is named Shekara. Now you know the meaning of the surname of Distinguished Senator Malam Ibrahim Shekarau from Kano.

A third example is Tanko. This is a child born after three female children. Variants include Gudaji, Tankari, Yuguda/Iguda/Guda. I am sure you know the famous Muhammed Gudaji Kazaure, a Member of the House of Representatives of Nigeria and his media presence in late 2022.

Each of these sampled names reflects a philosophical worldview, reflecting spiritual resignation or slight humour. They, therefore, encode the traditional Hausa perspective of living and dying as inscribed in the way they name their children.

Names that even the contemporary Hausa avoid because of bad collective memory are those linked to wealth and being owned or slavery.

Slaves have prominently featured in the political and social structure of the traditional Hausa societies, especially in the old commercial emirates of Kano, Zaria, Daura and Katsina. Their roles are clearly defined along socially accepted norms, and they are expected to perform given assignments demanded by their masters.

Slaves in Kano are divided into two: domestic and farm-collective. Trusted and, therefore, domesticated slaves are mainly found in ruling houses and are prized because of their loyalty to the title holder. Farmyard slaves were often captured during raids or wars and were not trusted because of the possibility of escape. They were usually owned by wealthy merchants or farmers and were put to work mainly on farms

Although the institution of slavery as then practised has been eliminated in traditional Hausa societies, the main emirate ruling houses still retain vestiges of inherited slave ownership, reflected even in the categorisation of the slaves. For instance, in Kano, royal slaves were distinguished between first-generation slaves (bayi) and those born into slavery (cucanawa).

At the height of slave raids and ownership, particularly when owning a slave was an indication of wealth, the names of the slaves often reflected the status of the owner. Examples of these names include Nasamu (given to the first slave owned by a young man determined to become a wealthy man), Arziki (first female slave owned by a man), Nagode (female slave given away to a person as a gift), Baba da Rai (first gift of a male slave to a son by his father), Dangana (male slave of a latter-day successful farmer or trader, although later given also to a child whose elder siblings all died in infancy. The female slave variant is Nadogara), and Baubawa (slaves with a different faith from the owner), amongst others.

The changing political economy of Hausa societies since the coming of colonialism has created new social dynamics, which included the outward banning of slavery. Thus, many of the names associated with slaves and ‘being-owned’ in traditional Hausa societies became disused, unfashionable, or, which is more probable, to be used without any idea of their original meaning. It is thought that some records of them may be of value. An example is ‘Anini’, usually a slave name but later used to refer to a child born with tiny limbs. The ‘smallness’ is also reflected in the fact that ‘anini’ was a coin in the Nigerian economy, usually 1/10th of a penny—a bit like the small Indian copper coin, ‘dam’ (from which the English language got ‘damn’, as in ‘I don’t give a damn’).

Further, with the coming of Islam, slave names were eased out and replaced by conventional Muslim names as dictated by Islam, Retained, however, are slave names that also served as descriptors of the functions of the slave, even in contemporary ruling houses. Examples of these slave titles, which are rarely used outside of the places, include:

Shamaki (looks after the king’s horses and serves as an overseer of the slaves), Ɗan Rimi (King’s top slave official and looks after all weapons), Sallama (King’s bosom friend [usually a eunuch], same role as Abin Faɗa), Kasheka shares the household supplies to king’s wives [usually a eunuch], Babban Zagi (a runner in front of the king), Jarmai (the head of an army), Kilishi (prepares sitting place for the king), amongst others. These names are almost exclusively restricted to the palace and rarely used outside its confines. Cases of nicknames of individuals bearing these names remain just that but had no official connotation outside of the palace.

The coming of Islam to Hausaland in about the 13th century altered the way traditional Hausa named their children and created the second category of Hausa beside the first ‘traditional’ ones. This second category became the Muslim Hausa, which abandoned all cultural activities associated with the traditional Hausa beliefs. This was not an overnight process. However, taking it as it does, centuries. Even then, a significant portion of Muslim Hausa material culture remains the same as for traditional Hausa. The point of departure is in religious or community practices, which for the Muslim Hausa, are guided by tenets of Islam.

Affected at this point of departure is naming conventions. This is more so because Islam encourages adherents to give their children good meaningful names. These names must, therefore, not reflect anything that counters the fundamental faith of the bearer or reflect a revert to a pre-Islamic period in the lives of the individuals.

However, while predominantly accepting Muslim names, traditional Hausa parents have domesticated some of the names to the contours of their language. For instance, Guruza (Ahmad), Da’u (Dawud), Gagare (Abubakar), Auwa (Hauwa), Daso (Maryam), Babuga (Umar), Ilu (Isma’il), amongst others.

So, here you are. If you are looking for an authentic, ‘clean’ traditional Hausa name or trying to understand your friend’s traditional Hausa name (or even yours), you are welcome to 1001 Traditional Hausa names.

The list is divided into two. The first contains 869 authentic traditional Hausa names. The second contains 132 Arabic/Islamic that the Hausa have somehow domesticated to their linguistic anthropology.

The file is available at https://bit.ly/42HJl97.