Fuel subsidy gone, but the borrowing floodgates are open

By Nasiru Ibrahim

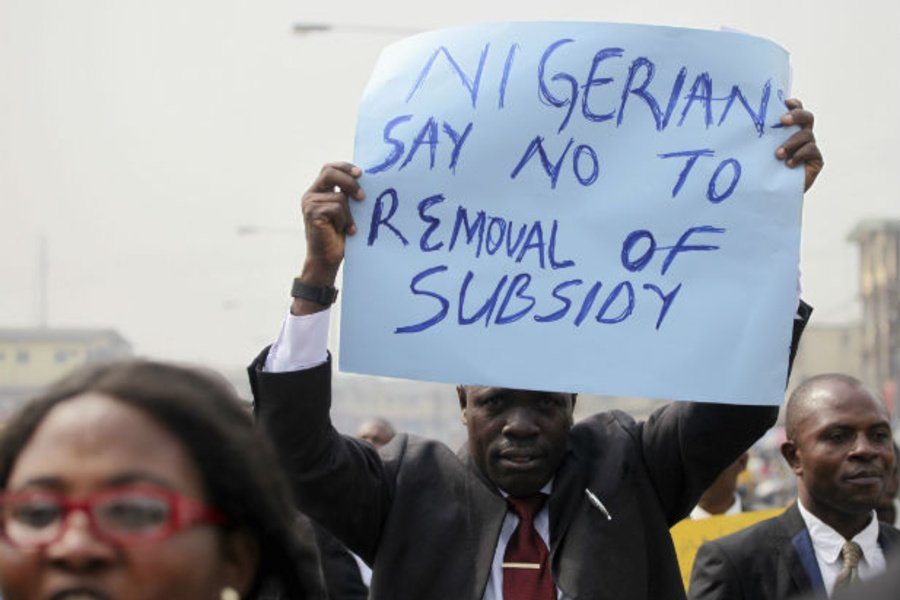

Nigeria’s debt situation has become more confusing and concerning in recent years. After removing fuel subsidies, which had always been used to justify heavy borrowing, many expected a change in direction. But surprisingly, debt has continued to rise—and sharply.

In less than two years, Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s administration has added over ₦62 trillion to our total debt. This comes on top of Muhammadu Buhari’s already heavy debt legacy. Yet if you check the 2025 budget, it still carries a huge deficit. This is despite relatively stable oil prices and a slight improvement in crude oil production. So, something is clearly not adding up.

How can a country that has removed one of its biggest expenditures—fuel subsidies—still be borrowing more than ever? Is it that the revenue reforms aren’t working, or is this a deeper issue with how we manage our economy? These are real questions that need honest answers. The reality is that Nigeria’s current borrowing trend is worrying not just because of the amount, but also because of the manner in which it’s happening and what it reflects.

According to the Debt Management Office, as of March 31, 2025, Nigeria’s public debt stood at ₦149.39 trillion. Tinubu alone has added ₦62.01 trillion to that figure in under two years. Now, let’s compare that with previous administrations: Goodluck Jonathan borrowed ₦5.9 trillion in five years. Buhari borrowed ₦74.78 trillion in eight years—including the controversial “Ways and Means” borrowing from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). That’s how bad things have gotten.

“Ways and Means” are short-term loans from the Central Bank to the Federal Government, intended to cover urgent expenses such as paying salaries or addressing unexpected shortfalls. Think of it like an overdraft facility. But the law is clear—the CBN Act, 2007 (Section 38) states that the Federal Government can only borrow up to 5% of the previous year’s revenue from the CBN, and it must be repaid in the same year. Under Buhari, this law was ignored. His government borrowed ₦22.7 trillion through Ways and Means, without obtaining proper approval from the National Assembly.

This ₦22.7 trillion had not been reflected in official debt figures for a long time. It only became part of Nigeria’s domestic debt record in May 2023, when Buhari’s government securitised it—basically converted it into long-term bonds. That move alone caused the total public debt to jump from ₦44.06 trillion at the end of 2022 to ₦87.38 trillion by June 2023. That’s a massive increase in just six months.

Now, some economists argue that Tinubu’s debt figures appear worse primarily due to the exchange rate. That argument is simple: Nigeria borrows in foreign currencies, such as the dollar, euro, or yuan, but records the debt in naira. So when the naira weakens, the same dollar loan becomes much bigger in naira terms.

Let’s look at the exchange rate across administrations. Under Jonathan, the exchange rate was around ₦ 157 to $1 in 2015. Under Buhari, the exchange rate was ₦770/$ in 2023. And under Tinubu, the exchange rate is now approximately ₦1536/$ as of 2025. So when you convert the same external loan, the naira value explodes as the currency weakens. Just this exchange rate movement has added ₦29.75 trillion to Tinubu’s external debt and ₦5.9 trillion to Buhari’s.

To properly check if the debt spike is mainly due to FX changes, let’s fix the exchange rate at ₦157/$ for all the administrations and see how much was actually borrowed. The formula is simple:

Old Dollar Debt × New Exchange Rate – Old Dollar Debt × Old Exchange Rate.

Using the DMO’s external debt figure of $38.81 billion in 2023:

$38.81bn × ₦770 = ₦29.85 trillion

$38.81bn × ₦1536 = ₦59.63 trillion

₦59.63 trillion – ₦29.85 trillion = ₦29.78 trillion

So, if the exchange rate had remained at ₦157/$, Nigeria’s external debt of $42.46 billion in 2025 would have been approximately ₦6.6 trillion. Under that fixed exchange rate, Jonathan’s total external borrowing would have been approximately ₦1.07 trillion over five years. Buhari’s about ₦4.48 trillion in eight years.

Tinubu’s about ₦1.12 trillion in under two years. This means if Tinubu continues at this pace, he’ll hit Buhari’s figure—₦4.48 trillion—in about eight years. Yes, the exchange rate plays a significant role. But that’s not the whole story.

Others argue that Tinubu’s debt problem is not just about FX. It’s also about spending discipline. Unlike Buhari, Tinubu removed fuel subsidies and slightly increased oil production (1.5–1.6 million barrels per day, compared to Buhari’s average of 1.2–1.3 million barrels), and customs and tax revenue also improved. Buhari faced more challenging conditions—global oil crashes, two recessions in 2016 and 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic, and high subsidy payments—during his early years. So, Tinubu had more room to save, but instead, borrowing has increased.

The 2025 budget projects a deficit of ₦13.08 trillion. It assumes oil at $77.96 per barrel and production of 2.06 million barrels per day. However, in reality, March production was only 1.65 million barrels per day, including condensates. And as of July 8, Brent crude was $70.20 and WTI was $68.42—both below the assumed price. That means revenue projections may fall short, and the government will likely borrow even more.

Tinubu has already requested $21.6 billion in new loans. In May 2025, Reuters reported that he also asked the National Assembly to approve loans of €2.2 billion, ¥15 billion (approximately $104 million), and an additional $2 billion in domestic loans. That’s not all.

The Federal Government also secured a $747 million syndicated external loan to fund Phase 1, Section 1 of the Lagos-Calabar Coastal Highway—from Victoria Island to Eleko Village. At ₦1536/$, this loan adds ₦1.147 trillion to the debt. The lenders include Deutsche Bank, First Abu Dhabi Bank, Afreximbank, and Zenith Bank, among others. The Islamic Corporation for the Insurance of Investment and Export Credit (ICIEC) is providing insurance. That brings Tinubu’s total borrowing to about ₦63.157 trillion in under two years.

This highway is being built under a Public-Private Partnership using an EPC+F model. The road is over 70% complete and is designed using CRCP technology—concrete with a 50-year lifespan and low maintenance requirements. While the loan adds to debt, it shows some confidence from global investors and introduces a financing model that shares risk between the government and private firms.

Now to the bigger picture. As of 2024, Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio is around 25.1%, based on ₦144.67 trillion in debt and a nominal GDP of about $375 billion. That means debt accounts for about one-quarter of the economy—not yet alarming, but becoming risky if borrowing continues at this rate. What’s more worrying is the cost of servicing debt.

In 2024, debt service took up 4.1% of GDP—up from 3.7% in 2023 (AfDB report). That’s a lot. Imagine 4.1% of the entire economy going towards just paying off debt, instead of building schools, roads, or hospitals. Even worse, the debt service-to-revenue ratio rose from 76.86% in 2023 to 77.4% in 2024 (APA News). This means more than three-quarters of government revenue is now used to repay debt. That leaves very little for anything else. That’s not sustainable.

As Economics graduates, the way forward is clear. First, we need to depoliticise how we manage public finances. Countries like Chile, Sweden, and the UK have independent Fiscal Councils that enforce rules like debt limits and balanced budgets. Nigeria needs something like that to restore discipline and rebuild investor trust.

Second, loans must be tied to development goals—not used for consumption. Borrowing should be used for essential services like roads, electricity, and digital infrastructure, rather than paying salaries or covering bloated administrative costs. Rwanda and Ethiopia have shown how debt used for infrastructure can boost exports and growth. A cost-benefit analysis should accompany every loan.

Third, we must cut waste and off-budget liabilities. That includes fuel subsidies, failing state-owned enterprises, and unauthorised bailouts. Ghana passed a Fiscal Responsibility Act in 2018, capped its deficit at 5% of GDP, and ran audits that exposed massive leakages. Nigeria can cut borrowing by 30–40% just by following that path.

Fourth, improve tax collection—not by harassing small traders, but through fairness and the use of technology. Indonesia raised its tax-to-GDP ratio by digitising filing, automating risk detection, and linking tax IDs with national identity numbers. Nigeria can do the same—target high earners and multinationals instead of informal workers.

Fifth, public-private partnerships and syndicated loans, such as the Lagos-Calabar road, shouldn’t be used to conceal debt. They should help us attract private capital, share risks, and deliver real development. Countries like Morocco and Kenya make their PPP contracts public. Nigeria should also strive for greater transparency.

Finally, if things get out of hand, we can consider debt restructuring—but only as a last resort and if tied to fundamental reforms. Ghana restructured its debt in 2023 by extending maturities and cutting interest under IMF guidance. But what made it work was reform—cutting subsidies and improving tax systems. Without reform, restructuring solves nothing.

This is the time for Nigeria to act. If we continue on this path, we are only postponing a more profound crisis. But with the right decisions, we can still change direction.

Ibrahim is a graduate of Economics from Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached via nasirfirji4@gmail.com.