By Nasiru Ibrahim

The channels of distribution from exploration to consumers in Nigeria’s oil industry—before Dangote’s refinery—began with crude oil extracted by NNPC Ltd. and international companies such as Shell, Mobil, and Chevron. The crude was sold to NNPC or exported. Due to the poor performance of local refineries, such as those in Warri and Port Harcourt, Nigeria relied on importing refined fuel through NNPC and major marketers, including TotalEnergies, Oando, and Conoil.

Once imported, the fuel was stored in depots like Apapa, Atlas Cove, Ibru Jetty, and Calabar. From there, independent transport companies such as Petrolog, TSL Logistics, AA Rano, and MRS transported it by tanker to filling stations. These stations—both major and independent—sold the fuel directly to consumers.

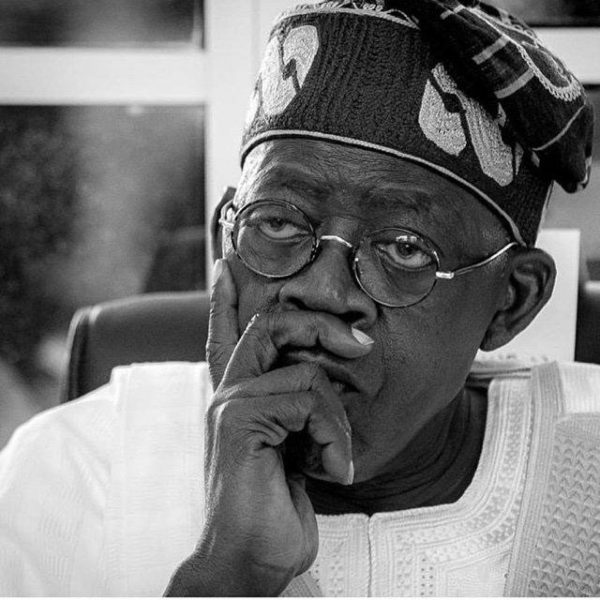

Alhaji Aliko Dangote is on the verge of taking full control of Nigeria’s downstream oil sector, covering everything from marketing and retail to transportation and distribution of petroleum products. In economic terms, this is known as vertical integration. Many Nigerians are now raising concerns that Dangote could dominate the entire fuel market. This comes after Dangote Petroleum Refinery released a press statement outlining its upcoming plans for fuel supply and distribution.

In the statement dated June 16, 2025, the company announced that it will start selling petrol (PMS) and diesel in the Nigerian market from August 15, 2025. To support this, it plans to roll out 4,000 Compressed Natural Gas (CNG)-powered trucks across the country to deliver fuel directly to buyers at no additional logistics cost.

Dangote also revealed that it will offer credit facilities to credible buyers who purchase at least 500,000 litres of PMS or diesel.

These buyers include registered oil marketers, manufacturers, telecom companies, airlines, and other large fuel consumers. The company states that this move will enhance fuel availability, reduce reliance on imports, and bolster Nigeria’s energy security by overseeing both refining and distribution.

With Dangote’s new initiative, he buys crude oil from NNPC and refines it here in Nigeria. Then, using his trucks, he moves the fuel to his storage depots and delivers it straight to filling stations. This means no need for middlemen or prominent marketers—everything is handled by Dangote’s team from start to finish.

However, while this could lower fuel prices and ease supply challenges, it has also sparked fears about reduced competition. Some worry that giving too much power to one player could lead to a market monopoly, calling for proper regulation to ensure fairness in the downstream sector.

Economists, policymakers, businessmen, entrepreneurs, and economics students like myself are actively considering the potential impact of this new initiative on oil marketers, the Nigerian economy, employment, exchange rates, consumers, filling stations, climate change, and other critical factors. Many are questioning whether this move will yield positive results. However, we cannot understand the implications unless we first examine the structure and components of Nigeria’s downstream sector, including Dangote himself, his competitors, those affected by his actions, and all other players in the supply chain up to the final consumer.

In economics and policy development, a long-standing debate exists about how policies should be evaluated. Some scholars argue that policies should be judged by their outcomes, while others believe they should be assessed based on their intentions. For example, Milton Friedman emphasised that policies must be judged by their results, not their intentions.

In contrast, economists like Paul Samuelson acknowledged the importance of considering both intent and context, especially when outcomes are not yet visible. This debate is relevant here. It may be premature to conclude whether Dangote’s new initiative is positive or negative solely based on expected results, as those outcomes have not yet materialised.

Nevertheless, some would argue that judging the initiative by its intention — such as improving fuel availability, reducing logistics costs, and enhancing energy security — is still meaningful, especially in economic policy, where many decisions are based on projected or long-term effects. Evaluating intentions enables us to gauge the direction of policy, even in the absence of immediate evidence.

Nigeria’s downstream sector is responsible for refining, retailing, distribution, transportation, and marketing of petroleum products. It comprises several companies and regulatory bodies, including NNPCL, Dangote Refinery, Oando, MRS, AA Rano, ExxonMobil, Danmarna, Aliko Oil, and many others. While Dangote operates across both the midstream and downstream sectors, his actions may also indirectly affect the upstream sector, particularly through their influence on demand, supply, and the pricing of petroleum products.

Instead of focusing solely on the structure of the downstream sector, I believe we should carefully consider both the potential benefits and drawbacks of this new initiative by Dangote Refinery, without completely dismissing Friedman’s view on judging policies strictly by results.

Potential Positive Implications of the New Initiative

Firstly, Dangote’s new initiative will reduce Nigeria’s dependence on imported oil from the Gulf and Europe. This is beneficial for Nigeria’s foreign exchange (FX) reserves, as less demand for imported fuel means the country will need fewer U.S. dollars for imports. As a result, this could lead to an appreciation of the Naira due to a fall in demand for foreign currency. Additionally, it will improve the trade balance and increase GDP contribution from the domestic oil refining sector.

Secondly, the initiative will create both direct and indirect jobs in Nigeria. Direct employment opportunities will arise for truck drivers, mechanics, technicians, depot workers, and logistics personnel. If Dangote deploys between 2,000 and 4,000 trucks, and each truck requires one to two drivers, along with at least one support mechanic, one depot staff member, and logistics coordinators, this could result in approximately 20,000 direct jobs. Indirect employment opportunities will arise for consultants, accountants, lawyers, filling station managers, as well as workers in catering, cleaning, petrochemicals, fertiliser, plastics, and related industries.

Thirdly, the initiative will enhance fuel accessibility and improve supply chain efficiency, thereby reducing waste and environmental pollution. By taking direct control over storage and distribution, the initiative can eliminate middlemen inefficiencies, potentially reducing fuel scarcity and hoarding, which often drive up inflation. With direct sales to filling stations, illegal practices like tanker swaps and product diversion by middlemen can be curbed. Furthermore, the use of Compressed Natural Gas (CNG)-powered trucks will lower transportation costs, reduce emissions, and increase domestic gas utilisation, thereby boosting gas revenue.

Fourthly, the initiative is expected to lower fuel prices, which is a major driver of inflation in Nigeria. By eliminating international shipping fees, foreign refinery profit margins, and import levies—all of which form a significant portion of the overall fuel cost—the retail price per unit of fuel could drop. Lower fuel prices can ease the cost of living, reduce inflationary pressures, and improve economic stability.

Fifthly, the initiative will strengthen Nigeria’s energy security in the face of global supply chain disruptions. For instance, ongoing conflicts such as the Israel-Iran and Russia-Ukraine wars, or geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, can threaten the global fuel supply. Additionally, OPEC+ efforts to raise oil prices increase external vulnerabilities. By reducing dependence on imported fuel, Nigeria becomes more resilient to global shocks, ensuring steady availability of fuel at domestic filling stations even during international crises.

Sixthly, from a broader perspective, this initiative positions Nigeria as a regional supplier of refined petroleum products in Africa, reducing the continent’s reliance on Europe and the Gulf. This shift enhances Nigeria’s foreign policy leverage and strategic influence, particularly within regional and international institutions such as ECOWAS, AfCFTA, AfDB, and Afreximbank. A robust domestic refining industry enhances investor confidence and may attract more foreign direct investment (FDI) in the long term. Investors are more likely to commit to economies with stable energy supply, regional trade advantages, and reduced exposure to global price shocks.

Potential Negative Implications

Firstly, there is a serious economic fear that this could lead to a monopoly, and many Nigerians have already raised concerns about that. The Petroleum Tanker Drivers and Owners Association of Nigeria (PATROAN) and the Independent Petroleum Marketers Association of Nigeria (IPMAN) have both expressed worry that Dangote might dominate the entire downstream oil sector. In economics, when a single company controls the whole supply chain, from refining to selling, it stifles competition. And when there’s no competition, prices can be fixed unfairly, small businesses get pushed out, and consumers suffer in the long run.

Secondly, there’s the risk of predatory pricing. This occurs when a powerful company sells at very low prices—sometimes even below cost—to drive smaller competitors out of the market. Dangote might do this since he doesn’t import fuel and can afford to sell at a lower price. However, after chasing them out, he can raise prices at any time, leaving people with no choice and putting consumers at risk of exploitation. This leads to what is called “deadweight loss” in economics, where both individuals and the economy lose out.

Thirdly, many jobs could be lost, especially among small fuel marketers, distributors, and transporters who previously imported and sold fuel themselves. Dangote is now doing everything directly—refining, distributing, and even retailing—which means companies like AA Rano, Danmarna, Aliko Oil, and many others might be pushed out or forced to operate under unfair terms. This is already affecting their businesses, especially in the North, and could lead to job losses in areas that rely heavily on these companies.

Fourthly, government policy interference and the role of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL) could create more problems. NNPCL also operates in the downstream sector and has partnerships and influence that could either support or conflict with Dangote’s activities. Past issues, such as unclear pricing, fuel subsidy mismanagement, and delays in policy implementation, demonstrate that when government agencies operate without transparency, it can create more confusion than solutions. This could make it easier for big companies like Dangote to influence decisions in their favour while others suffer.

Fifthly, new investors might avoid the sector. If one company already controls everything, what’s left for others to invest in? People may view the fuel business in Nigeria as a “one-man game,” making it challenging to attract new ideas, competition, and investment. This can slow down innovation and limit the country’s long-term progress in energy.

Sixthly, there’s a risk of regional imbalance. Dangote might focus more on high-demand urban areas where there’s more profit, and this could lead to fuel shortages in rural or northern regions. Small marketers who once served these communities may not survive, and that means remote areas could suffer more from fuel scarcity. This may exacerbate existing regional inequalities.

Possible solutions

Firstly, don’t ban fuel imports immediately. Let other marketers continue importing fuel, at least for the time being. If only one company controls the supply, prices may rise or stay unstable. The government can grant import waivers to others, ensuring that competition remains alive and fuel remains affordable.

Secondly, we should repair our old refineries and support the development of new ones. Dangote shouldn’t be the only one refining fuel. If we repair the Warri, Port Harcourt, and Kaduna refineries and encourage small private ones, we’ll have a more local supply. That also helps in the future if we want to export after meeting our own needs.

Thirdly, ensure that other players can access storage and transportation facilities. If only Dangote had the port, pipelines, and trucks, smaller marketers wouldn’t survive. The government can step in to make sure these facilities are shared fairly, with clear rules and affordable fees.

Fourthly, don’t forget far places like Northern states and rural towns. Most fuel may remain in the South, where Dangote is located. Therefore, the government should support distribution to remote areas by encouraging group buying or establishing shared fuel depots. Everyone deserves access, not just those near the refinery.

Fifthly, expand the availability of fuel alternatives like CNG to more locations. If we’re shifting to compressed natural gas (CNG), it should not be exclusive to the rich or city dwellers. Rural and remote areas require the same support,including CNG buses, filling stations, and awareness initiatives.

Finally, monitor prices and ensure fairness. We need a simple system that tracks and shows fuel prices across regions. That way, if one company tries to raise prices unfairly, the public and the government will be aware.

Ibrahim is an economist and writer based in Jigawa State, Nigeria. He holds a degree in Economics from Bayero University, Kano. With a background in journalism at Forsige, he currently works as a research assistant and contributes expert commentary on economics, finance, and business.