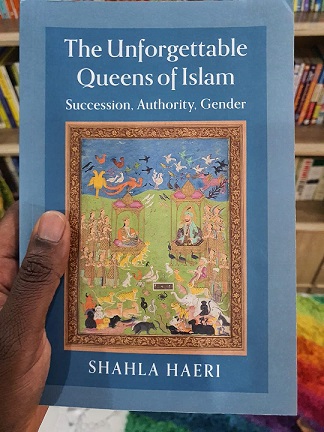

Book Review: The Unforgettable Queens of Islam

By Dr Shamsuddeen Sani

It’s very easy to ignore this book. Underrate it even. I found myself rereading it for many days, given the enormous importance of the topic, especially in the contemporary discourse in Muslim-majority countries about woman’s leadership. Being a recent publication in 2020, and although the author didn’t explicitly state it, it appears to be building to improve upon earlier work by the late Moroccan feminist writer and sociologist Fatima Mernessi with her book, The Forgotten Queens of Islam.

Shahla Haeri embarks on a journey of gendering the historical narrative of sovereignty and political authority in the Muslim world, shedding light on the lives of Muslim women leaders who defied the norms of dynastic and political power to rise as sovereigns in their deeply patriarchal societies.

The author’s usage of the term “queen” is not meant to be taken literally for all six prominent figures discussed in the book but rather to signify their immensely influential leadership roles during their respective eras. While recognising the significant impact of numerous women in Islamic history who exerted influence behind the scenes, Haeri emphasises those women who stood at the forefront of the political machinery, actively engaging with the structures of authority and power.

She doesn’t just relay the historical milestones of these great women in historical Islam but brings in a fresh perspective on how we look at the concept of women’s leadership in the Islamic tradition. The author situates women rulers’ rise to power within three interrelated domains: kinship and marriage, patriarchal rules of succession, and individual women’s charisma and popular appeal.

This book prompts deep contemplation on patriarchy within the pre-modern normative Islamic tradition. But one needs to be careful because the author appears to be overly problematising patriarchy in some instances significantly beyond what we consider as would have been normal in pre-modern Islam. She did allude, however, to the critical role of men in women ascending to positions of political authority.

Structurally, this book has a Preface and Introduction and is broken into three main parts with two body chapters. Part I, Sacred Sources of Authority: The Qurʾan and the Hadith, lays the background for her accounts, with a deep examination of the primary sources of the Qurʾan and hadith, through the Qurʾanic story of the Queen of Sheba and the biography of the Sayyida Aisha (RA). Haeri relays the Quranic account of the dramatic encounter between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, popularly known as Bilqis. Drawing primarily from Tha’alabi and al-Tabari, the book cross-examines the sovereignty of Bilqis and connects the Quranic revelations with what she believes was the exegetes’ medieval patriarchal reconstructions.

Part II of the book is about Medieval Queens: Dynasty and Descent. In Chapter 3, the book explores the leadership life of the long reign of the Ismaili Shiite Yemeni queen. It examines Queen Arwa’s fascinating political acumen and how she survived the political and power succession tussle dealing with the 3 Fatimid caliphs of Cairo. Chapter 4 examines the short sovereign rule of the only female sultan of the 13th century Delhi Sultanate, Razia Sultan: ‘Queen of the World Bilqis-i Jihan.

The 3rd part of the book, which explores the contemporary Queens and examines the institutionalisation of succession, provides an in-depth look at Benazir Bhutto and Megawati Sukarnoputri but will not spoil more here for the interesting details in the book.

Haeri concludes this work of ethnohistory which is deeply personal as she peppers in the concept of the “paradox of patriarchy,” which refers to the historical tradition of power succession among men, particularly fathers and sons, or even brothers, whose family ties legitimise the customary transfer of power. She quickly alludes that the relationship between fathers and sons can be a source of tension and rivalry, where they may fear, resent, or even seek to eliminate each other. In contrast, father-daughter relationships tend to be more personally fulfilling and have fewer political consequences for the father. The preference of patriarchs for their daughters is not only driven by self-preservation but also by their recognition of their daughters’ talents and political astuteness.

Dr Shamsuddeen Sani wrote from Kano. He can be reached via deensani@yahoo.com.