By Prof. Abdalla Uba Adamu

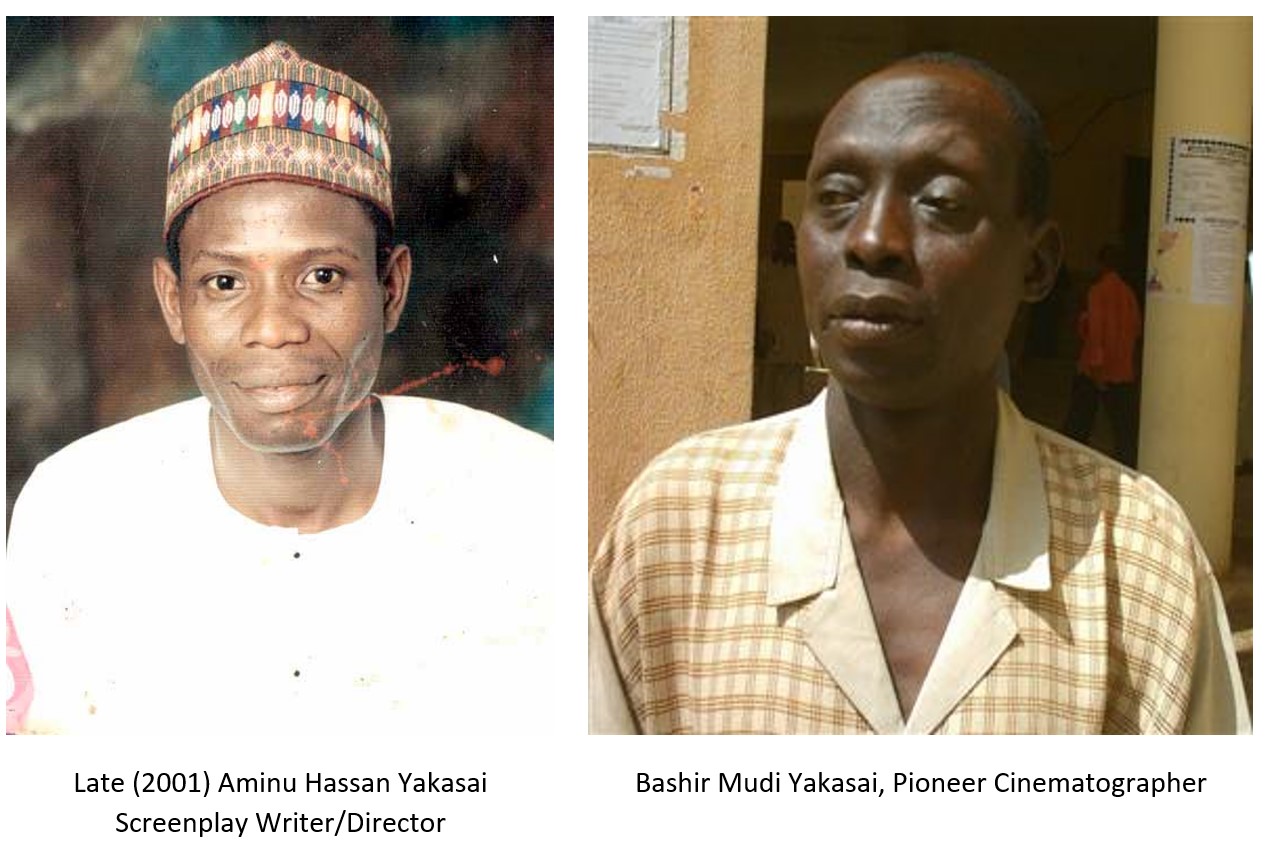

An industry is a system made up of interconnecting parts that synchronise together to create a perfect dynamic and functional entity. However, there is a central creative focus. Thus, while no one can claim to have been the actual originator of commercial Kannywood since many people – and processes contributed to its development – nevertheless, the creative spark that lit the fire of Kannywood was the late novelist Aminu Hassan Yakasai. If one person can be credited with creating the industry, it was him and only him.

In the late 1970s, the Nigerian film director Ola Balogun directed two successful Yoruba films. The first, “Ajani Ogun”, was co-produced with the actor Ade Love. The second, “Ija Ominira”, starred Ade Love. Hubert Ogunde, a famous Yoruba travelling theatre showman, decided to join the trend. He invited Ola Balogun to direct Aiye, which was hugely successful and led to a follow-up, Jaiyesinmi.

These Yoruba films found their way to Kano’s bustling “stranger” (or, more appropriately, “guest settlers”) communities of Sabon Gari in the 1980s, where they were shown in cinemas and hotel bars. This attracted the attention of Hausa amateur TV soap opera stars and crew, such as Bashir Mudi Yakasai (cinematographer), Aminu Hassan Yakasai (scriptwriter) and Tijjani Ibrahim (director). Surprisingly, despite the massive popularity of Hausa drama in television houses and government financial muscle, the idea of full-scale commercial production of Hausa drama episodes by the television houses was never considered. Individuals wishing to own certain episodes simply go to the television station and pay the cost of the tape and a duplication fee, and that was it. There was no attempt to commercialise the process on a full scale.

In the same period, the northern cities of Kano, Kaduna, and Jos benefitted immensely from the massive transfusion of modern media influences caused by not only a liberal society but also the tolerant interaction of diverse cultures and religions in the same public spaces. They were, undoubtedly, the creative hubs of northern Nigerian popular culture. Jos was famous for its vibrant nightclub and music scene. Kaduna also had a rich musical heritage, coupled with a TV culture. Kano was more muted and relied on music and club life inflows to Sabon Gari from other regions.

However, one aspect of popular culture Kano had that was absent in Kaduna and Jos was prose fiction. While other cities were grooving the night away, residents of Kano were burning the midnight oil. The first published modern Hausa fiction was “So Aljannar Duniya” by Hafsat AbdulWaheed from Kano in 1980`. It opened the floodgates and led to hundreds of novelists creating a whole genre of African indigenous fiction referred to informally as Kano Market Literature.

Also, at the same time, Kano had many drama groups that enjoyed stage plays that were often improvisational and not based on any script but with a general focus on social responsibility. These drama groups became spawning grounds for those who established the Kannywood film industry. These included Tumbin Giwa Drama Group (Auwalu Isma’ila Marshall, Shu’aibu Yawale, Ibrahim Mandawari, Adamu Muhammad, Ado Abubakar, Jamila Adamu. (Gimbiya Fatima), Hajara Usman, Ɗanlami Alhassan, etc.), Jigon Hausa Drama Club (Khalid Musa, Kamilu Muhammad, Fati Suleiman, Bala Anas Babinlata), Tauraruwa Drama & Modern Film Production (Abdullahi Zakari Fagge, Shehu Hassan Kano, Iliyasu Muhammad, Hajiya Rabi Sufi, Auwalu Ɗangata, Ado Ahmad G/Dabino, Asama’u Jama’are), and Hamdala Drama Wudil ( Its members include Rabilu Musa Ɗanlasan (lbro), Mallam Auwalu Dare, Ishaq Sidi Ishaq, Bappah Yautai, Bappah Ahmad Cinnaka, Haj. Hussaina Gombe (Tsigai), Shua’ibu Ɗanwamzam, Umar Katakore etc.) There were many more, of course, but these were foundational to Kannywood.

The TV shows from then Radio Television Kaduna were gripping and inspiring to these drama groups. TV show stars that became role models to these Kano drama groups included Ƙasimu Yero, Usman Baba Pategi Samanja, Haruna Ɗanjuma, Harira Kachia, Hajara Ibrahim, Ashiru Bazanga (Sawun Keke) and others.

Thus, it was that at the time of producing Bakan Gizo in Bagauda Lake Hotel 1983 to 1984 Aminu Hassan Yakasai, Ali “Kallamu” Muhammad Yakasai, Bashir Mudi Yakasai started strategising creating a drama for cinema settings (thus Kannywood was often seen as the creation of a ‘Yakasai Mafia’ as those from Yakasai dominated its creative direction!).

The tentative title of the film they were thinking of shooting was to be called Shigifa. It was a story of four unemployed graduates thinking about setting up a company – a departure from the romantic or comedic focus of then-then-popular TV shows. A script idea was floated, and Aminu Hassan Yakasai was to be the scriptwriter. However, before the idea matured, the group started getting contracts for video coverage of social events, etc. Actually, part of the coverage was also stored as footage, although the film was not eventually made.

The precise decision to commercialise the Hausa video film, and thus create an industry, was made by Aminu Hassan Yakasai in 1986, with technical support of Bashir Mudi Yakasai, the leading cinematographer in Kano, and Tijjani Ibrahim, a producer with CTV 67.

Aminu Hassan Yakasai was a member of the Tumbin Giwa Drama Group. He was also a writer and a member of the Raina Kama Writers Association, which spearheaded the development of what became known as Kano Market Literature in the 1980s. Thus, the idea of putting Hausa drama—and extending the concept later—on video films and selling it was a revolutionary insight, simply because no one had thought of it in the northern part of Nigeria. The project was initiated in 1986, and by 1989, a film, Turmin Danya, had been completed. It was released to the market in March 1990—giving birth to the Hausa video film industry. Salisu Galadanci was the producer, director, and cinematographer, while Bashir Mudi Yakasai provided technical advice.

The moderate acceptance of Turmin Danya in Kano encouraged the Tumbin Giwa drama group to produce another video, Rikicin Duniya in 1991 and Gimbiya Fatima in 1992 — all with resounding success. By now, it was becoming clear to the pioneers that there seemed to be a viable Hausa video film market, and this viability laid the foundation of the fragmented nature of the Hausa video film industry. While organised groups formed to create the drama and film production units, individual members decided to stake out their territories and chart their future. Thus, Adamu Muhammad, the star of Gimbiya Fatima, decided to produce his own video film, independent of the Tumbin Giwa group in 1994. The video film was Kwabon Masoyi, based on his novel of the same name, and outlined the roadmap for the future of the Hausa video film. At the same time, it sounded the death knell of the drama groups. This was because Aminu Hassan Yakasai, who created the very concept of marketing Hausa video films—and thus created an industry—broke away from Tumbin Giwa and formed Nagarta Motion Pictures. Others followed suit.

Other organised drama groups in Kano did not fare too well either. For instance, Jigon Hausa, which released a genre-forming Munkar in 1995, broke up with the star of the video film, Bala Anas Babinlata, forming an independent Mazari Film Mirage production company (Salma Salma Duduf). Similarly, Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino broke away from Tauraruwa Drama and Modern Films Production (which produced In Da So Da Ƙauna) and formed Gidan Dabino Video Production (Cinnaka, Mukhtar, Kowa Da Ranarsa). While Garun Malam Video Club produced Bakandamiyar Rikicin Duniya, written by Ɗan Azumi Baba, after the video film was released, Baba left the group and established RK Studios (Badaƙala).

From field studies and interviews with the producers in Kano, most of these break-ups were not based on creative differences but on financial disagreements or personality clashes within the groups. The number of officially registered “film production” companies in Kano alone between 1995 and 2000 was more than 120. There were many others whose “studio heads” did not submit themselves to any form of registration and simply sprang into action whenever a contract to make a film was made available.

Interestingly, Adamu Muhammad of Kwabon Masoyi Productions produced the first Hausa video film entirely in English. It was “House Boy”. Although it was an innovative experiment by a Hausa video filmmaker to enter into the English language video genre, it was a commercial disaster. Hausa audience refused to buy it because it seemed too much like a “Nigerian film”, associating it with southern Nigerian video films. When the producer took it to Onitsha—the main marketing centre for Nigerian films in the south-east part of the country—to sell to the Igbo marketers, they rebuffed him, indicating their surprise that a Hausa video producer could command enough English even to produce a video film in the language. Further, the video had no known “Nigerian film” actors and, therefore, was unacceptable to them. Thus, the Hausa audience rejected it because it looked too much like a “Nigerian film”, while non-Hausa left it because it used “unknown” Hausa actors, so it must be a Hausa film, even though the dialogue was in English!

Tragically, Aminu Hassan Yakasai died in an automobile accident on Saturday, June 16, 2001, on his way to Katsina to participate in a film, “Arziki da Tashin Hankali”.