By Abdullahi Abubakar Lamido

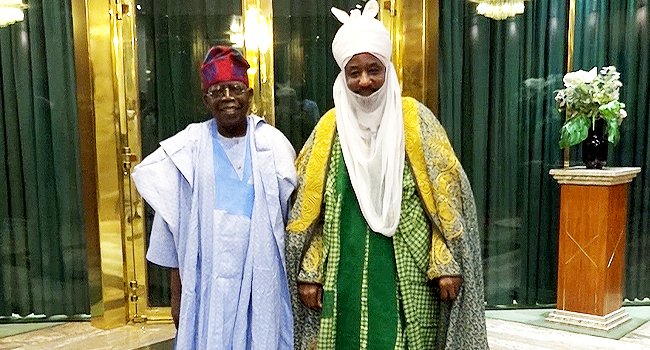

The history of Islam – and religion in general – in post-colonial Nigeria is incomplete without a detailed analysis of the Muslim Students Society of Nigeria (MSSN). All the important Muslim figures, including politicians like Sir Ahmadu Bello Sardauna and MKO Abiola; scholars like Sheikh Mahmud Gummi, Sheikh Sherif Ibrahim Saleh and Sheikh Dr. Ahmed Lemu; intellectuals like Professor Oloyede, Dr. Usman Bugaje, Malam Ibrahim Sulaiman and Prof. Salisu Shehu; traditional leaders like Emir Muhammadu Sanusi II of Kano, Emir Maigwari of Birnin Gwari; Aree Musulmi Abdul Azeez Arisekola Alao; accomplished Muslim women like Alhaja Latifat Okunnu and Hajiya Aisha B. Lemu or distinguished business persons and technocrats; will all have a mutilated history of religious engagement if the chapter of their engagement with the MSSN is removed from their biographies.

These people (mentioned above) interacted with the MSSN as mentors, some as members, some as patrons, others as leaders, and so on. However, their relationship with the MSSN is vital because it is direct, mutually beneficial, and socio-religiously impactful. In case you did not know, the MSSN nominated Sheikh Abubakar Mahmud Gummi for the prestigious King Faisal International Award. When Hajiya Aisha Lemu came to Nigeria, she asked her husband, Sheikh Lemu, to link her up with the MSSN. And so is the story with almost every educated Muslim in Nigeria.

As an intellectual, reformist, ideological, moderate and resilient Islamic movement, the MSSN, in the last 70 years, remained the primary engineroom of Muslim intellectual development and the religious focus for Muslims. MSSN promotes the pursuit of Western-style education without compromising the Islamic faith. It encourages Muslims to learn from the West without being Westernized, to pursue “secular” education without embracing secularism, and to excel in all specializations without deviation. In MSSN, people learn how to learn, plan, earn, and live a life of faith, health, and wealth. It strikes a balance between the spiritual and the mundane, the worldly and the otherworldly. MSSN, in short, is a blessing to the Muslim Ummah and the entire Nigeria.

The primary operational arena of the MSSN has always been the academic institutions. While secondary schools are the recruitment centres of new members and the place where they are vaccinated with a sufficient dosage of spiritual, ideological and moral training, the higher institutions, particularly Universities, have remained the bastions of advancing the intellectual capacity, religious consciousness, leadership acumen and civilizational alertness of Muslim students. The Universities, in particular, have been the arenas where the philosophy of MSSN is built, its vision formulated, its projects designed, its programmes implemented, its members developed, its objectives pursued, its impact felt, and its strength consolidated. This has been the case since the 1960s when it was only about a decade old.

In this regard, three universities in particular distinguished themselves as the strongholds of the MSSN in its early history (especially from the 1970s to the 1980s): Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), University of Ibadan (UI) and Bayero University Kano (BUK). Details of how this happened are beyond this piece. But what suffices here is the fact that ABU and BUK took centre stage as the rallying point of young MSSN intellectuals, especially those who grew to be (among) the topmost Muslim intellectuals of the North, especially from the 1970s, at the peak of the booming days of communism and Marxism on Nigerian university campuses. It was then that emerging scholars like Malam Ibrahim Sulaiman, Dr Hamid Bobboyi, Prof. Auwal Yadudu, Dr Usman Bugaje, Prof. Ibrahim Naiya Sada, and a host of other MSSN leaders took the pen and the pain to counter the bane of the Ummah: they faced the challenge posed by the anti-religious radical left-wing Marxist socialist intellectuals. They wrote papers, presented lectures, engaged in debates, published magazines, made press releases and participated in on-campus and off-campus national discourses.

At the peak of the intellectual engagements of the MSSN in the late 70s came the Iranian Revolution. Since MSSN is an Islamic reformist movement, it was easy for it to join the global Muslim community in celebrating the emergence of the Iranian Revolution spearheaded by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979 while the first generation of the MSSN intellectuals had graduated from the universities, even as they maintained contact with the Society’s leaders and members.

When Ibrahim El-Zakzaky, who was then the Vice President (International) of the society and among the few remaining older members on campus, represented it at an event in Iran, little did anyone know that the visit would open a new chapter not only in the MSSN movement but in the entire history of Islam in Nigeria. What did he do in Iran? How was he received? How did he receive their reception? What did he do after his return home? How, when, where did he start promoting Shiism? What was the reaction of the MSSN intellectuals? What then happened? The answers to these and many related questions are still scantly discussed, even in the highly scanty historical documentation of the MSSN itself. This is despite the importance of that discourse in the history of MSSN and Islam in Northern Nigeria.

By April 18 2024, MSSN had turned 70 years in its history. As part of the celebration of the Platinum Jubilee, a book was launched with the title MSSN @ 70: The Evolution, Success and Challenges of the “A” Zone, Northern States and the FCT. In this book, many actors like Dr. Usman Bugaje, Prof. Idris Bugaje, Barr. Muzammil Hanga, Alahaji Babagana Aji, etcetera shared illuminating perspectives about the MSSN in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. The book provides valuable insights into the events that culminated in El-Zakzaky’s embracing Shiism and his subsequent everlastingly irrevocable divorce from the MSSN. The book contains a rich rendition of events in the MSSN. Due to this, I wrote its review (on June 6 2024) on Facebook, mainly referring to El-Zakzaky’s Shi’ism-MSSN matter.

In the review, I referred to “how El-Zakzaky clandestinely planned to divert the MSSN to Shiism and how men like Dr. Bugaje and others were able to tackle him and save the Society from his sinister objectives”. But that led to a fascinating written conversation with Dr Abdulbasit Kassim; that bookworm was highly prolific and inquisitive but often interpreted by some as a “controversial” emerging Nigerian intellectual. Dr. Kassim is interested in African Islamic movements and has written extensively on important contemporary topics like Boko Haram, Salafism, Arabic manuscripts, Islamic intellectual developments in sub-Saharan Africa, and other issues. He raised questions. Our elder scholar-intellectual, Malam Ibrahim Ado-Kurawa, made clarifications. I responded. And the conversation continued. I share the interesting scholarly engagement with you here verbatim.

Dr. Abdulbasit Kassim wrote:

“Brilliant and timely! This book is an excellent sequel to Professor Siraj Abdulkarim’s “Religion and Development: The Muslim Students’ Society of Nigeria and its Contribution to National Development,” published in 2014. I highly recommend that MSSN A Zone create a digital archive of all the issues of Radiance Magazine and other publications published throughout the 80s and ’90s. If digitized, this repository would be a vital primary source collection for those seeking to learn more about the evolution of the organization and the ebbs and flows of ideational shifts of its leaders.

“While I wait to read this book, I have a brief comment about the oft-repeated attempt to single out Zakzaky for his supposed “clandestine role of smuggling Shiism into MSSN.” This framing of Zakzaky, in my opinion, is a half-truth. A close reading of all the catalogue of articles our fathers published in the 80s and 90s about the Islamic Revolution in Iran belie the narrative they sometimes portray about their ignorance of the creedal orientation of the Iranian government.

“Zakzaky was not a lone actor in that milieu. Several leaders of the MSSN, including my honoured father, Mallam Ibraheem Suleiman, wrote articles in New Nigerian, Triumph Newspaper, and Radiance magazine that were covertly and overtly sympathetic to Shiism. On March 3 1989, Dr Aliyu Tilde wrote “On the Path,” praising Zakzaky for leading the Iranian-style Islamic revolution in Nigeria. Dr Tilde wrote this letter nine years after Zakzaky publicly espoused his Shii affiliation at the Funtua Declaration on May 5 1980. Inayat Ittihad, the spokesman of the Iranian Revolution, was a regular keynote speaker at the International Islamic Seminar on Muslim Movements organized by MSSN at BUK in the early 80s. Inayat was public about his Shii creedal orientation. He preached the “Khomeini Model” to the MSSN members. At the same time, Sayyid Sadiq Al-Mahdi advocated for the Mahdiyya model in the struggle to achieve Islamic change.

“Although most MSSN leaders have embraced new ideological currents, it is important for our fathers to be honest in acknowledging their transitional phases and the seismic shifts in their orientations rather than scapegoating Zakzaky alone. The ebb and flow of ideations was not limited to Pantami alone. The التراجعات was a common feature of all the prominent Muslim figures in the 80s and 90s, including Mallam Ibrahim Ado, whose translator’s introduction of Jihad in Kano captured the prevalent thought in that milieu. Even Zakzaky has passed through different ideological phases, such as Mallam Abubakar Mujahid et al. It is important to tell the complete story and explain the nitty-gritty nuances.

“I hope this book sheds light on the relationship between MSSN and IIFSO. I am also quite curious to read what the MSSN leaders wrote about the ideological proteges of Aminu Kano and the firebrand radicals who inherited the radical struggle against the feudal rulership in northern Nigeria, the likes of Balarabe Musa, Abubakar Rimi, Gambo Sawaba, Bala Muhammad, Sule Lamido, Ayesha Imam, Bala Takaya, Shehu Umar Abdullahi, Bala Usman and Yohanna Madaki. Some of these figures were the ideological adversaries of the MSSN leaders.

“Congratulations to you, Abdullahi Abubakar Lamido. May Allah reward all the contributors who have documented the history of MSSN.

The following is my repose:

Dr. Abdulbasit Kassim!

Thank you for this intervention. As always, I like your consistency in trying to checkmate our intellectuals, especially what you see as their “methodology” of rendering historical narratives, which often presents “half-truth” and “belied” narratives. I believe your intervention is a continuation of your championing of suppressed history. Of course, just as you question these scholars and activists for always trying to give “half-truth” or one-sided aspects of history, so are others quick to read the same bias in virtually all your interventions on such matters. But that is what perspectives always mean.

You see, while I like us always to try to query narratives and ensure we get all the bits of it to have a comprehensive, nuanced reading of history, I doubt if defending the supposed “other side” at all costs will help us either. What seems clear is that you mistake being “sympathetic” to the Iranian Revolution or the “Khomeini Model” as being the same as accepting the “creedal orientation” of Iran. This, indeed, is misleading. Again, what escapes you is that Zakzaky never agreed to accept that he was Shia at that early time. He, in fact, “overtly and covertly” rejected being associated with Shi’ism. He was always quick to insist he was Sunni, Maliki. You can check that. However, even the Iranians who kept sending books to the students only sent books on Revolution, governance, justice, civilization, etc.

By the way, I have not seen in your intervention here any substantial evidence to support your claim that “a close reading of all the catalogue of articles our farmers published in the 80s and 90s belie the narrative they sometimes portray about their ignorance of the creedal orientation of the Iranian government”. What I expected to see was where Malam Ibraheem Suleiman, Dr Tilde or any one of them declared or promoted the Shiite creed, not just showing sympathy to Iran. And I still need evidence to understand how “Zakzaky was not alone in that milieu”. Who and who were with him in promoting Shi’ism at that early stage? At least those “our fathers” have told us that not sooner than Zakzaky returned from his visit to Iran did they realize he had shifted from only romancing the Iranian Revolution to promoting strange ideologies. Immediately, people close to him started to caution the younger ones. And what I found in the narrative of Malam Baba Gana Aji in the MSSN @ 70 book is how Zakzaky got the opportunity, after most elders had left campus, to be virtually the only elder around and, therefore, take total control of contact with the younger ones.

Now, is it also part of the “belied” narratives that El-Zakzaky was alone when he started organizing what came to be known as “extension” after the Islamic Vacation Course (IVC)? Who was with him, please? Is it also “half-truth” that people like Dr Bugaje and others who later formed the Muslim Ummah were against him immediately after Zakzaky started his Shi’ism? Any evidence to the contrary? Is it also not true that people like Ustaz Abubakar Mujahid only continued to be with Zakzaky for some time because they liked the Iranian Revolution even as they disliked the Iranian Ccreed Are you saying there were no people who followed Zakzaky for some time while insisting they were Sunnis? Why were some people called yan karangiya by those in Zakzaky’s camp due to their anti-Shiism-pro-revolution posture even later?

It is good that we study the issues and learn more about history than our assumption of reading “all the catalogue of articles” from the 80s and 90s. When we do so, perhaps we will be more educated about the matters and then see the apparent difference between sympathizing with the Iranian Revolution and embracing Shi’ism, especially at that time.

But the fact that the MSSN was a group of people trying to bring societal change based on Islam, it should not be difficult for one to understand how easy it was for the MSSN to sympathize with whoever declared an Islamic Revolution at that time. By the way, praising and sympathizing with the Iranian Revolution was a common thing in the Muslim world, even among the global Sunni population. Even Azhar scholars could agree to work with Iran to unite Muslims and many of them after the Revolution. Scholars like Sheikh Yusuf Al-Qaradawi also joined their call for taqreeb. They only abandoned that project and often declared them hypocrites or so after discovering that they were using that to spread their Shiite creed. Could these scholars accept the “creedal orientation of the Iranian government”?

You see, to date, some of the older MSSN people will still insist that they like the “Khomeini Model” of establishing an Islamic government, but they never like his creedal “model”. At least you have read one from one of our elders here.

So, please, let’s expand our reading of the issues and understand them more.

Mal Ibrahim Ado Kurawa wrote:

“Professor Abdulbasit Kassim, I agree with you entirely, even though I haven’t been privileged to see the MSSN book. It is not unusual for people to follow different trajectories. I visited Iran in 1983. I didn’t like their Shiism but still respect their Muslim solidarity, so we indeed need a complete story. When the Iranians came to Nigeria, they didn’t begin by openly preaching Shiism. They even promised to translate the books of the Sokoto Jihad leaders, which they had never done then. They began propagating Shiism after Zakzaky accepted to become one. My last physical encounter with Zakzaky was in Makkah in 1984. Some of us left him to seek knowledge in Egypt and Saudi. Therefore, I cannot recall what transpired thereafter.”

After the above intervention by our elder brother, Dr. Abdulbasit Kasim wrote

“Jazakallahu Khairan Amir Abdullahi Abubakar Lamido. May Allah reward you for your intervention and continue to guide and direct our affairs. Amīn. There is a famous saying that فللسؤال أهمية كبرى في طلب العلم فالأسئلة مفاتيح العلم (questioning is of great importance in seeking knowledge, for questions are the keys to knowledge.). This phrase is similar to what Imam al-Bāqillānī said العلم قفل ومفتاحه المسألة (Knowledge is a lock. And its key is questioning) and the well-known saying of Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī العلم سؤال وجواب (Knowledge is question and answer). The key to knowing for a seeker of knowledge is to ask questions with بلسان سؤول وقلب عقول (the tongue of a questioner and the heart of a thinker).”

My previous submission is devoid of malicious intent (an apology for the use of the word “belie” or “half-truth”) or an attempt to validate predetermined frames and outcomes. Instead, it is solely aimed at reconciling competing and sometimes contradictory interpretations of events that took place in the past. Alhamdulillah, no figures in MSSN I described as honoured fathers have ever ascribed ulterior motives to my questions. Since 2006, they have continuously accommodated the micro-details I pick up on and the torrent of questions I submit. I am indebted to them for granting me access to their libraries, encouraging critical historical questions, and helping me and other younger folks better understand where we are coming from and how we got where we are now. May Allah reward them abundantly in this world and the hereafter. Amīn.

”How do we know what happened in the past? This mutual exchange is aimed at reading against the grain, reading between the lines, paying attention to what is not said, and listening to silences and absences by carefully engaging in comprehensive evaluation and chronological interrogation of a portfolio of primary sources generated contemporaneously that provide evidence or first-hand testimonies about the events in the 80s and 90s. While we respect our honoured fathers for their service to Islam, we must ask questions and subject the verbal and written testimony of events they present to us to thorough scrutiny by weighing, cross-referencing, or bringing their accounts into conversation with other disparate source materials and distinct authorial perspectives. This was the intent of my submission.

”The 11th February Revolution of Khomeini had a global appeal in the Muslim world. It had the Bin-Laden effect. What started as hysteria over the successful defeat of the Western colonial powers and their Arab secular puppet (the Shah regime) later transitioned into disillusionment after the creedal orientation of Khomeini became self-evident despite his call for Islamic unity. In Nigeria, the timeline of events could be traced from January 1980, when Zakzaky visited Iran and was reported to have personally met Imam Khomeini on his sickbed, to July 10 1994, when Shaykh Abubakar Mujahid and his followers in JTI successfully broke away from Zakzaky.

“There was clear opposition from the MSSN leaders towards Zakzaky’s attempt to spread Shiism. This position was made clear by Shaykh Abubakar Mujahid during his 1998 interview when he said:“When he (Zakzaky) started he had not got any feeling towards Shiism. But at one point, when he started collecting money from Iran, they started bringing Shiism. What we did, we said no. Their beliefs and our beliefs are not the same. We operate the Mālikī School of Thought. They operate the Jaʿfarī School of Thought, so a clash will occur. Why don’t we go on with our revolutionary zeal, which was gaining momentum at the time, rather than bring this Shia? The people at the beginning were accusing us of being Shia, which we were not. Then they understood we weren’t so they started joining, and if we turned around and became Shia, we would be deceiving them. In 1989, he came back from prison in Port Harcourt. When we saw these moves in Shiism, we started to preach against them. That is, the members of the group who were entering Shiism, we preached against them, saying we are not Shia. We will not do Shiism, we will do the Maliki School of Thought.” [End of Quote]

“Before gaining further clarity from you, Amir, and our honored father, Mallam Ibrahim Ado, I struggled to reconcile the clear oppositional stance of the MSSN leaders towards Zakzaky’s Shiism with their admiration and reproduction of articles on the central tenet of the “Khomeini Model of Islamic Governance,” which revolved around the concept of “Wilāyat al-Faqīh.” My brain could not process why MSSN leaders would preach against Shiism yet write editorials and articles on Wilāyat al-Faqīh – a political theology Khomeini popularized in Iran with copious citations from the works of Shi’i theologians, including Mullah Ahmad Naraqi, Muhammad Hussain Naini, and Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr. If I could recall accurately, Mallam Ibraheem A. Waziri and Dr. Muhammad S Balogun once had an exchange about this subject in the past.

“No doubt, our honored fathers yearned for Islamic models for societal change. They read and learned about Muslim movements across different historical periods, seeking a common method of formation, mobilization, and strategy that Muslims could utilize in the struggle to achieve Islamic change. The Khomeini, Fodiawa, and Mahdiyya models were some of the models they wrote about in the 1980s and 90s in their attempt to awaken the Muslim population to Islamic societal change.

“What I learned from this exchange is that even when the MSSN leaders wrote about the “Khomeini Model of Islamic Governance” and the concept of “Wilāyat al-Faqīh,” they approached the idea as a political model without embracing the Shi’i creedal component Khomeini deployed to legitimize the concept as a political theology.

“Let me conclude by saying once again Jazakallahu Khairan for providing safe spaces of dialogue and intellectual engagement where curious seekers of knowledge can ask the who, what, where, when, why, and how historical questions without invoking the binary of he belongs to “our side vs. their side” or “us vs. them” dichotomies. As Ibn Hazm said صفة سؤال المُتعلِّم هو أن تسأل عمَّا لا تدري لا عمَّا تدري (The characteristic of a learner’s question is to ask about what they do not know, not about what they do know.) The more we ask questions and try to reconcile competing ideas and narratives, the more we gain a comprehensive picture of the past.

Abdullahi Lamido responded

Abdulbasit Kassim Masha Allah Prof. May Allah reward us all and bless our little efforts. You know, we are all passengers in the train of never-ending learning or what is called life-long learning. Interestingly, that is the first thing we learnt from the MSSN; that learning begins from the cradle and only ends in the grave. So, we always pray to Allah for more knowledge using the “And say O Lord increase me in knowledge” formula. We “ask those who know” so as to unlearn, learn and relearn.

Through our usual lengthy, fruitful phone engagements with you (which often take us between two and four hours), I know that you are not only a scholar but one who is serious about learning. I have also understood that your questions are born out of an insatiable curiosity, a burning desire to know more and more and more. And I understand this further through your acceptance of every single issue where stronger evidence becomes clear to you. Unfortunately, not every social media friend of yours has the opportunity to have such heart-to-heart, deep, mutual scholarly engagements with you.

However, the more interesting thing to me is the quantum of knowledge I gain from you via such amicable, mutual exchanges. I often deliberately bombard you with questions to trigger powerful, fact-supported responses that are usually backed by numerous references from books I have never read. I do not even have the time and energy to read them. You read too much!

Back to the “Khomeini Model” and the “Wilayat al-Faqih” question. As you rightly said, Wilayat al-Faqih is essentially a political concept and a convenient political instrument Khomeini used to establish the legitimacy of his Revolution and government. It is not fundamentally a theological concept. That is why he was comfortable spreading it even before starting to export his Shiite creed. And by the way he needed it at that time…

Secondly, you seem to think that our fathers who were in the MSSN at that time had a prior sufficient knowledge of what Shi’ism entailed. No. Shi’ism had never been present in our community. So, nobody knew it. After all, those our fathers were not even necessarily deep in the knowledge of Sunnah and even the dominant Maliki jurisprudence back then. Their main sources of Islamic knowledge were the English translations of ikhwan books coming from Egypt and those coming from Pakistan. You should not expect them to just easily detect the traces of Shi’ism by mere reading a seemingly innocent political concept even when it was supported by Shiite authorities who, by the way, were not known here.

I thank you very much and pray that this useful intellectual discussion will continue. And I look forward to reading your review of the MSSN @70 Book Insha Allah.

Greetings to the family.

Wasallam

Finally, Dr. Abdulbasit Wrote

“Jazakallahu Khairan Amir Abdullahi Abubakar Lamido. May Allah reward you for helping me and other young folks to better understand the complexities of the history of Islamic thought.

“Thank you for being generous with your time. I appreciate your patience and willingness to clarify all the torrent of questions on Wilāyat al-Faqīh that came up during our lengthy phone conversation.

“May Allah reward you and all our fathers at MSSN who served the organization with the sole aim of uplifting the Dīn. May Allah bless the publisher, editors and contributors who worked on the book project. In sha Allah, I look forward to learning more from you and all our honoured fathers.

“As promised, In sha Allah, once I receive the copies of the MSSN @70, I will distribute the book to different libraries where more people can access, read, and cite it in their research and writing.

“Extend my Salam to the family.

Wa Alaykum Salam.”

Conclusion

I have learned from the above engagement that there is a need to write more about the MSSN and its evolution and contributions to national development. A lot is missing and in need regarding the written history of MSSN and other Islamic organizations in Nigeria. May Allah bless our little efforts and grant us enormous rewards for them.

Abdullahi Abubakar Lamido can be contacted via lamidomabudi@gmail.com.