By Abubakar Muhammad Tukur

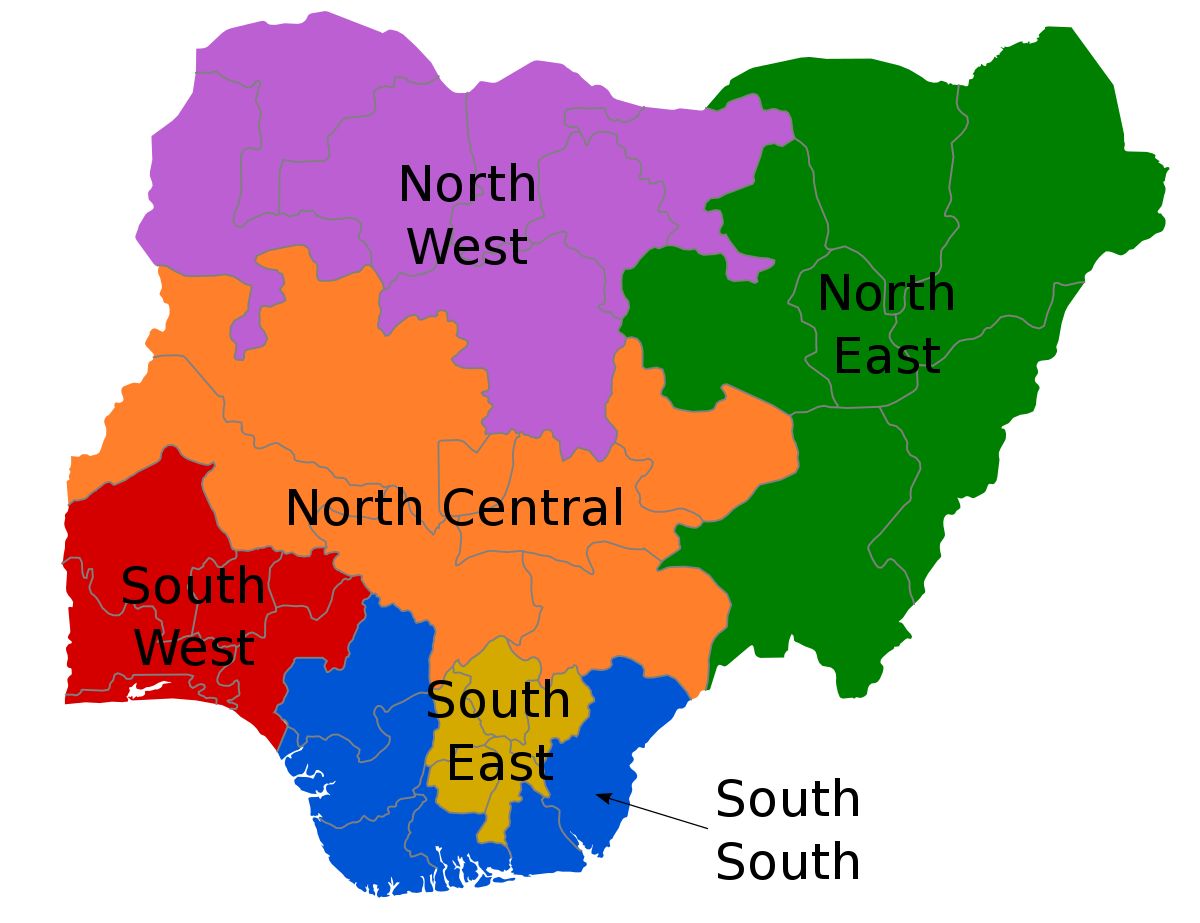

In Nigeria, true federalism means different things to different people. The newfound phrase could be better understood using a geo-political lens. Let us begin with the southwest, which the Yoruba dominates.

The agitation for true federalism started in the southwest immediately after the annulment of the 1993 presidential election, believed to have been won by a Yoruba man. The Yoruba elite argued that the election was annulled simply because their northern counterparts were unwilling to concede political power to the south. Hence, their vigorous campaign for a ‘power shift’ to the south. By power shift, they meant an end to the northern elites’ stranglehold on political power and, by extension, economic control.

However, with a Yoruba man, Olusegun Obasanjo, emerging as the president in 1999, the clamour for a power shift became moribund and was replaced with that of ‘true federalism’. By true federalism, the Yoruba elite means a federal system with a weak centre, a system in which the constituent units are independent of the centre, especially in the fiscal sphere.

The cry of marginalisation has been loud in the southeast, home to the Igbo ethnic group. The Igbo’s position regarding Nigeria’s federal system is that the system is characterised by lopsidedness, particularly in allocating national resources.

Another ground of Igbo agitation for true federalism is their perception of non-integration into mainstream politics since the end of the civil war in 1970, citing a lack of federal presence in the region. This sense of lack of belonging informs the views of some pro-self-determination groups like the Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) and Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) that the Igbo people are no longer interested in being part of Nigeria and should be allowed to secede and form an independent state of Biafra.

It is, however, doubtful if the campaign for the resurgence of Biafra is popular among the elite of the southeast whose political and business interests cut across the country. By true federalism, therefore, the Igbos of the southeast mean a federal practice that accommodates every ethnic group in the multinational federation.

Similarly, a sense of political and economic marginalisation forms the basis upon which the minorities in the Niger Delta (or the south-south geo-political zone), where the bulk of Nigeria’s oil is located, persistently demand their own exclusive political space using the euphemism of ‘resource control’ and true federalism.

In the Nigerian context, the term resource control means the right of a federating unit to have absolute control over the mineral resources found within its jurisdiction and contribute to the central government to fund federal responsibilities.

The perceived injustice in resource distribution is the main driving force for the struggle for resource control. The oil-producing states have repeatedly argued that Nigeria’s fiscal federalism, which encourages lopsided distributive politics, has been unfair to them. For the people of the Niger Delta, therefore, resource control is a solution to marginalisation. Thus, for the people of this region, true federalism means a federal practice whereby the federating units are allowed to own and manage their resources as they desire.

Seemingly, the northern elite wants the status quo to remain based on the belief that the present system favours its interest in some quarters. These include the federal character principle, majority representation at the federal level and quota system.

We have been able to demonstrate in this article that central to the agitations for true federalism in Nigeria is the struggle for access to national resources. Oil rents and their distribution have shaped the operation of Nigeria’s federal system and have also contributed largely to the failure of federalism in Nigeria. Nigeria’s history of revenue distribution is about each ethnic group or geo-political region seeking to maximise its share of national resources. One reason for the acrimonious revenue allocation system is that Nigeria’s component units lack viable sources of revenue of their own.

Also, the economic disparity that has given rise to unequal development among them is another source of contention. Therefore, any future political reform must ensure the accommodation of the country’s ethnic diversity because this is one of the many ways national unity could be achieved.

As a way out of the over-centralisation of the system, the country’s fiscal federalism should emphasise revenue generation rather than revenue distribution, as this would ensure the fiscal viability of the states. Any future reform should be tailored towards the states generating their own revenue, and those not endowed with resources should devise strategies to generate revenue from other sources. Internally-generated revenue should only complement a state’s share of federally collected revenue. Moreover, with the decentralisation of economic resources, the states would be in relative control of their resources and be less dependent on the centre.

A weakening of the federal centre may not be a bad idea, but Nigeria needs a federal system that would ensure the relative supremacy of the central government vis-à-vis the state governments. The size of the federation, as well as its ethnic diversity and economic disparity, requires a relatively strong federal government that would be able to regulate the competition for national resources.

It may be concluded at this juncture that Nigerian federalism is defective, and reforms are inescapable. The unending quest for true federalism, political restructuring, and self-determination within the context of the ethnically heterogeneous Nigerian federation will disappear until the political leaders reform the institutions and structures of the federal system to give a semblance of genuine federalism.

Abubakar Muhammad Tukur, LLB (in view), can be contacted via abubakartukur00396@gmail.com.