By Umar Sheikh Tahir (Bauchi)

Columbia is an Ivy League University, one of the eight most prestigious institutions in the United States of America. Ph.D. students at this university undergo two years of coursework. One of the classes I took was Islam, Knowledge and Forms, which a visiting professor from Germany taught. Part of the course is a library visit to the exhibitions section under the project of Islamic Sciences, Science, Nature, and Beauty: Harmony and Cosmological Perspectives in Islamic Science (2022) at Butler Library, the largest library of Columbia University with millions of resources.

The exhibition contained objects, images, rare manuscripts, and other learning materials. Two materials, among others, became the most astonishing factors in the exhibition: one of them is a rare copy of the Holy Quran, and the second is a locally handmade wooden tablet (Allo).

The instructor asked everyone to talk about any material in the exhibition. Students gave their feedback on the experiences passionately; different things wowed everyone. When it came to my turn as someone who had known these items since childhood in my father’s private library, where we sneaked as children, which housed similar treasures. To us, these are the most useful items in his library as we do not read books; we only view images and magazines, such things that are not viewed as essential to the readers. Then, I shared my familiarity with these items, telling them I was exposed to most of the exhibited materials from my upbringing in Northern Nigeria, including “rare manuscripts” of the Quran.

The Quran displayed was a giant copy of the original Uthmanic Quran, denoted to the third Caliphate of the Muslim nations who reigned (644/23H–656/35H). It was so amazing to all of us. As for me, the Quran is the most frequently read book in my entire life, and to their surprise, I can read this copy fluently without diacritical marks. I highlighted that memorising the holy Quran, even without understanding Arabic, is common in Northern Nigeria. Most of my fellows never knew that sometimes people memorise it at an early age. I did not shock them with that, as I am one of them.

In the second incident, Professor Brinkley Messick invited me to speak in his class on Islamic Shariah Law as someone with experience with an Islamic Madrasa background and went to Azhar University in Egypt. The theme of the class is the Islamic madrasa. He is interested in the Islamic tradition, as evident from the cover of his book, “Calligraphic State.”

The Professor brought Allo a wooden tablet to the class and circulated it to students. Everyone was looking at it with surprise. I named it to them as a personal tablet for inscription and memorisation of the holy Quran, and the students asked for more details. I said we write verses from the holy Quran for memorisation after repeating it several times; not everyone understands how that works, except those with Islamic background. However, when I told them when we wash the script, we drink it, everyone was left with open mouths, surprising our embodiment of the holy book, including the professor. They could not process as modernised individuals with high sensitivity to germs and bacteria. Again, as I told our class last semester, this is very common in Northern Nigeria.

Coincidently, one of the attendees from a Saudi background added that people used some scripts for Talismite and protection from Djinn (Ruqyā in Arabic or Ruqiyya in Hausa) by reciting some verses in water. I told her this is true; we have that part in our culture too, but the biggest part is that we drink washed script for the embodiment and show respect for not letting a drop of that water on the ground as a sacred word. As kids, we were told that whatever verses we memorise from the holy Quran and drink will stay in our hearts for a long time.

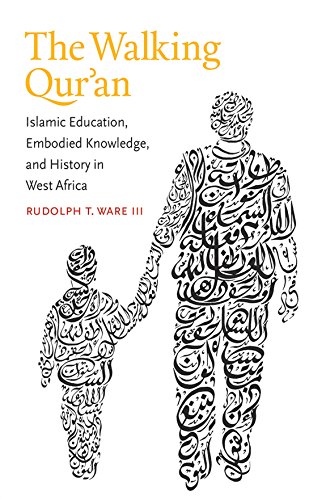

In reference to that, American Professor of Islam in Africa Rudolph Ware published his book Walking Quran on the Madrasa system in West Africa. He referred to those Quranic students’ embodiment as the Walking Quran in relation to the narration of the Hadith reported in the books of Hadith such as Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim; Aisha was asked about Prophet Muhammad’s PBUH character, and she said he was a Walking Quran.

Our cultural legacy, often undervalued by some of us in our region, gained recognition at Ivy League institutions. Those people appreciate a centuries-old Quranic educational tradition or Almajiri system and show their respect to our subregion. Even our way of drinking the washed script of the Quran mesmerised them.

A professor dedicated his projects to studying a school system called Daara schools in Senegambia or the Tsangaya schools in Northern Nigeria, making it evident that our legacy is an astonishing point to those communities. Then, as indigenous Africans who were introduced to the colonial system of Education less than a century ago in Northern Nigeria, we should be more proud of our system by appreciating those communities who choose to preserve it, as they make our subregion a central point of high intellectual conversation around the world.

We should not deny our legacy by stigmatising the Almajiri system of education. Instead, we should support it and create a way of modernising it to empower and preserve our centuries-old legacy. Whoever shows kindness to the Quran and its reciters will receive people’s applauses in this life, including Western intellectuals, and God’s reward in the hereafter. Thanks to those state governments in Northern Nigeria who support and recognise this system of education.

Umar Sheikh Tahir is a PhD student at Columbia University, New York, USA. He can be reached via ust2102@columbia.edu.

Umar’s recounting of his experience at Columbia, particularly within an Islamic Studies class, sheds light on the astounding reactions of Western academics to elements of his upbringing that are foundational yet often overlooked. Among the lesser-known aspects highlighted in the article is the reverence for the Holy Quran within Northern Nigerian culture. He unveils the tradition of memorizing the Quran at a young age, a practice not widely understood by those outside the Islamic background.

Furthermore, he uncovers the use of a locally crafted wooden tablet, referred to as “Allo,” for inscribing and memorizing verses from the Quran—a practice that fascinated and surprised Western students and professors alike. His narrative delves into the cultural significance of this tablet, revealing the customary act of washing the script and drinking the water as a symbol of embodying the sacred text. The astonishment of his peers at this tradition highlights the dichotomy between modern sensibilities and age-old customs rooted in reverence for the Quran.

It is impressive how he beautifully, showcases the convergence of traditional cultural practices with modern academic scrutiny, inviting a reevaluation of indigenous educational systems in Nigeria and their significance on a global stage. It sheds light on the richness and depth of Northern Nigerian culture, underscoring the importance of preserving and celebrating these enduring traditions in today’s evolving educational landscape. This insightful perspective offered through his experiences at an Ivy League institution, should open a dialogue that bridges the gap between tradition and modernity, urging recognition and support for the cultural legacies that shape societies worldwide.

I love this article from the Sheikh’s son. Well, I also attended Madrasa where we used Allo to read and write and I can’t count how many times I’ve drank the written Qur’anic verses on the slate. So, I don’t find any contradiction in what he said. Though, others might find but it’s exactly what I’ll say that he said already. Although, I don’t think this is done in every part of the northern Nigeria. However, this is also done in north central Nigeria; mine was in Benue State where I grew up and attended Madrasa. And I’ve seen people who have memorized the glorious Qur’an from writing, reading and drinking written verses from the slate (Allo) in my Madrasa which I almost did. People also use it for talisman and no doubt, I’ve seen situations and instances, but the question should be: do these talisman really work?

John Paden in the acknowledgement of his magnum “Religion and political culture of Kano (1976)” stressed the need for the younger generations (children and students of Kano scholars) to live up to the responsibilities of continuing the legacies of their forebears.

Maulana Sidi Tahir the transitioned with modernization of societies by ensuring wards provisions are given to ensure he studies without Bara(begging) and parents take responsibility of his studies as God intended. He has done enough to set a pace for transformation of the program by his children/students into an institutions that can boast of alumni of Technocrats, Academicians, Business Men and women that are huffaz. Championing this paradigm shift will bring about improved human capital development across the north and preservation of the almajiri system as handed by our forbearers and improved to present realities.

It is amazing reading a scholarly work of sort from a scholar of Muslim extraction in Nothern Nigeria. Though I may no longer subscribe to certain views expressed by the writer, it is noteworthy to state that myself did pass through the same “makarantan Allo” in Benue state, north central Nigeria where the norm was not different from the writer’s expression.

What a piece Masha Allah keep it up

What a good piece! The write-up is so interesting as it highlights and vindicates Northern Nigeria’s Islamic tradition of learning the Glorious Qur’an by heart through the use of the wooden slate (Allo) at a very tender age. Though, like many commenters, I don’t subscribe to the opinion laid out by the writer. However, his ability to take our traditional Islamic culture across the border is noteworthy.

MashaAllah. No knowledge is ever a waste. Far away from home, the doctrines you were accustomed to ‘ has indeed proven to be of historical value across the whole world. I am super proud of the line of study you choose and most importantly the fact that you put your whole life Towards the path of the prophet. SAW. Allah ya Kara jagora da Basira