By Lawal Dahiru Mamman

Ann Soberekon, a retired laboratory scientist, was almost lynched by a mob in Port Harcourt following an accusation of witchcraft. Ann was actually suffering from dementia – a condition of the brain characterised by impairment of brain functions such as memory and judgment that interferes with doing everyday activities.

The incident led a rights group, Advocacy for Alleged Witches, to decry the ill-treatment meted out to those with mental health challenges. According to the group, the attribution of dementia and other mental disorders is rooted in irrational fear, misinterpretation and ignorance of the cause of disease.

Living in fear of being called names and other forms of stigmatisation is the way people with mental health issues live in Nigeria and even other African countries. Mental disorders are viewed as spiritual attacks, and patients are mirrored as those under the influence of evil spirits, bewitched or hexed. The only way to cure the world of such back in the dark days and put victims out of their mystery is to send them 6 feet down, while in more recent times, stigmatisation and other forms of inhumane treatment are dished out to mental health patients forcing them to instead of seek for solution drown in their unfortunate circumstances.

With the proliferation of knowledge of mental health, some African nations started signing Bills to protect the right of people suffering from mental health issues. Foremost among are countries like South Africa which signed the Mental Health Care Act 17 of 2002 on October 28, 2002, which then took effect on December 15, 2004, to cater for treatment and rehabilitation of persons with mental health illness. In 2012 Ghanaian government signed Mental Health Act 2012 into law. Zambia signed its Mental Health Act in 2019, and then in June 2022, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta signed the Mental Health Bill into law.

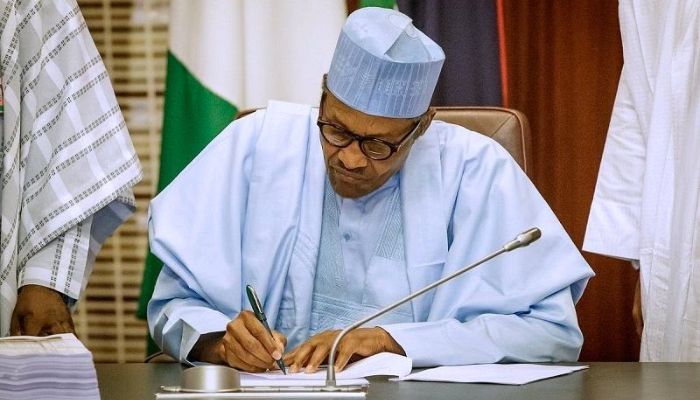

Nigeria followed suit when President Muhammadu Buhari, as a parting gift, bequeathed Nigeria on the 5th day of January 2023 the long-awaited Mental Health Bill by signing it into law, repealing heretofore extant law, which was known as the Lunacy Act CAP 542, of the laws of Nigeria 1964.

This is coming after the Bill has failed two attempts. Firstly, it was after the presentation in the National Assembly in 2003 before its withdrawal in April 2009 and secondly, in 2013 when the National Policy for Mental Health Services Delivery set out the principles for the delivery of care to people with mental, neurological, and substance abuse problems, but it was not signed into law.

The Mental Health Bill is a piece of legislation that covers the assessment, treatment, care and rights of people with mental health disorders while also discouraging stigmatisation and discrimination by setting standards for psychiatric practice in Nigeria, among other provisions.

The assent of the law generated a positive response, with physicians saying the law will afford those in the field the power to work unhindered and also enlighten Nigerians of the dangerous lifestyles that may lead to a breakdown in one’s mental health.

Doctor Olakunle Omoteemi, a physician in Osun State, said, “Due to the negative perception attached to mental health issues in Nigeria, the society still sees any case related to it as that of lunacy, and as a result of this negative perception, individuals shy away from making known, discussing or approaching professionals to discuss or reveal their mental health status.

“People also often cannot go for counselling based on the prejudice from the society. There is also the issue of stigma attached to it, as people are afraid to be called certain names. With this law, it is hoped that the prejudices and stigma attached to mental health issues will be laid to rest.”

The World Health Organisation (WHO) said at the 2022 World Mental Health Day on the 10th of October that One Hundred and Sixteen million (116,000,000) Africans suffer from one mental health disorder or another, and according to the President of the Association of Psychiatrists in Nigeria (APN), Taiwo Obindo, over sixty million (60,000,000) Nigerians agonise from mental illnesses.

Since the Bill this time around was not allowed to fade in oblivion, it will be safe to say ‘it is better late than never’ considering the statistics of the WHO and that of the president of APN. What is left is for those responsible for the bill to take charge in ensuring that the purpose for which the bill was signed is not defeated.

Lawal Dahiru Mamman, a corps member, writes from Abuja and can be reached via dahirulawal90@gmail.com.